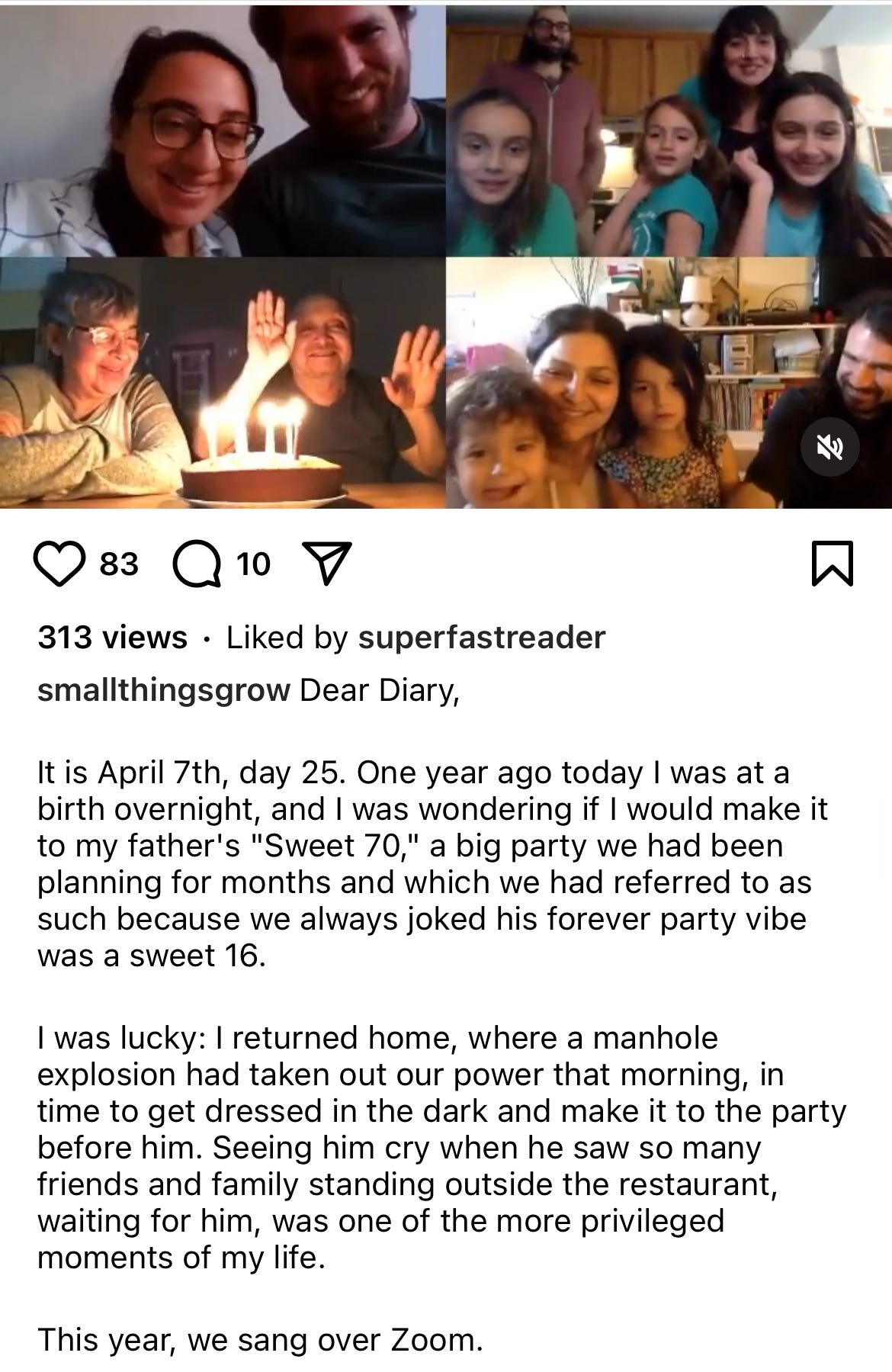

For a brief period during COVID lockdown in 2020, I posted daily writing on my personal instagram account that I called “diary entries.” These started on April 5th, day 23 of lockdown, and continued, more or less uninterrupted, until day 79 of lockdown, when I posted picture of Ilan and me during one of the protests of George Floyd’s murder. That is when my diary entries ended, because in the wake of the uprisings, it began to feel too self indulgent and myopic to spend my time musing about the fears and joys of grocery shopping during a global pandemic, or celebrating birthdays when you cannot throw a party, or the peculiar narrowing of the subject of my dreams, or the challenges of being a midwife in a health landscape where we knew nothing.

When I think about a moment in my life in which writing was both a lifeline and, simply, a joy, it is, improbably, often those months. I loved crafting those 2200 character snippets of my day, loved the ritual of trying to find something to write about in a vast expanse of mundanity. It was a specifically interior kind of writing, because the exterior was so limited — less so for me than anyone else I knew, because of births, but still, so much more limited than it had been — and the challenge of trying to write about something that was so intimately mine while also speaking to feelings that were universal was medicine, a dose of something that connected me to the vital beat of my own tender heart during a time when I could often feel it going ghostly, subsumed by the immediacies of trying to be the steady presence a lot of people needed me to be.

I could say I’ve been thinking about these entires a lot lately, but to say lately would be inaccurate; really, in the last four years, I am always thinking of them. Because I love the archive of them, but also because in some ways they represent a practice and discipline that seems so out of reach now. Who was the self who was able to write those, night after night? I reflect on the mundane little moments those entries captured and the ways in which my memory of that time is now sharper than it could be, because I wrote about it, and then I bemoan the fact that there are so many memories in between that are dimmer than they could be, because I didn’t write about them. Without diary entries like that, I wonder, will I remember the way Hanif says “blanket” (“blinkit”) or the tender, somehow both mournful and cheerful way he draws out his “byyeeeeeee” as he waves his chubby little hands? Will I remember the tears that spilled over my cheeks, the gasping hiccuping laughs me and Wren and Andy and Jo shared, when l came across this line in an article about chukar partridges?

Will I remember, really remember, the joy of finding something satisfying to feed my nearly 6-foot 14 year old and his friend after they showed up unexpectedly and I panicked, thinking the fridge was bare? Will I remember the look in his friend’s eye when he said, “oh no, no it’s okay I’m not hungry,” or the way I needed to do nothing but smile incredulously for him to admit, “well, I mean, maybe a little?” The feeling in my heart when he said that, the way it expanded knowing he knew he could admit it because I would always be good for a meal? Will I remember how in our postcolonial lit seminar a couple of weeks ago, during a discussion about the definition and characteristics of the very term “postcolonial,” I asked if anyone could think of whether it had any limitations and immediately turned to Wren to say, “Wren you usually find a problem in terms like this, so why don’t you start?” Will I remember the way she tossed her head and the way I halfway expected her to groan at me, to take offense, to object to being pigeonholed, or the way she took a deep breath and said, “Well,” emphatically, barely missing a beat before she beautifully interrogated the idea of “defining a people by what was done to them?”

I constantly wonder, could I do it again, could I just take a picture every day and write one thing, even just one small thing, about each and every day? And, I know, though I hate it, though it seems this should not be the answer, that the answer is no. Part of the reason I ever could, part of the reason I ever had what one might call a dedicated journaling practice in varying moments of my life, was because I had a time and space to do it that no longer exists. In the case of these COVID entries, for example, I was writing during a period that was, for all its challenges, in retrospect languorously and luxuriously slow. I was also writing on an Instagram account of that was “followed” by 500, but actually read by fewer, most of whom I knew personally. While I at the time appreciated that my friend Maggie called them “Smithsonian level archives,” and while the truth is that I’ve always needed the feeling of connection to maintain a steady writing practice, have always needed to write to someone who might recognize themselves in what I was feeling or voicing or explaining, it didn’t really occur to me then to wonder or care how many people saw the value in the entries. I wrote them for me, to stay connected to my heart, and that they did the same for others was both integral and also incidental. It did not matter if 10 or 100 people liked them; it only mattered that someone was theoretically there, on the other side of the words, that maybe they would write something back. My words, my little snippets of my life, were enough. Inherently. It never would have occurred to that Robina that eventually I’d write on a platform with an audience of nearly 25,000 (or that “nearly 25,000” would be a relatively paltry, unimpressive number in a world of something called “influencers”), that I might pause over what I would share of my kids with 25,000 strangers, that I might fret over what they wanted to read and whether anything I could say would be worth their presence at all.

What if I just write, I asked in my last newsletter.

And the me from three weeks later is asking, when? About what?

My friends, the truth is, I am struggling, and not just with that question.

I think most of you know — because my bitterness of this fact has not mellowed, not even a little, in nearly two years — that Andy lost his tenured professorship at the very end of 2023. We had spent nearly two decades investing in that goal for him (a journey I wrote about here ), only to have some bad real estate deals by a university that functioned, like most universities increasingly are, more like a corporation than a university to undo it all. (My bitterness around the more than 1 million dollar settlement the president who made those bad deals was awarded even as the university voted “no confidence” and fired her has mellowed even less. How many tenured faculty’s careers could have been saved with that money?) But what I’m only realizing now is that, as we worked toward that goal — and the mirrored-but-diverging goal of my own PhD, then midwifery degree, then midwifery career — we were also building our foundation as parents, as partners, as humans in the world. Andy was an academic as we had our first three children, as we made the decision to homeschool them, as we made the decision for me to pursue midwifery. We learned to be a family with him as an academic. I learned what it is to be a midwife with him as an academic. This is how we know how to raise kids and manage a household and do all the stuff of living. It is the foundation on which we structured the whole rest of our lives.

Now, he is working for the city (in a job he loves, in a job he gleefully describes as “trolling Eric Adams for a living”) and he has lost most of the flexibility and independence of academia. He is expected to show up at regular hours. He has “vacation time” and fills out a timesheet and can’t work in the crevices around homeschooling and midwifing. He has meetings and work events and lunches with coworkers and a commute. He had these things as an academic, too, of course, but less…relentlessly.

This shift has left me as the primary homeschooling parent to two high schoolers, one of whom is doing college applications, and a middle schooler. While I also work full time as a midwife. While I also nurse a two year old all night and chase him around all day.

I am, to say the least, destabilized.

I am only just now, nearly two years later, realizing the magnitude that was the earthquake of him losing his professorship, all the ways it had reverberated beyond the simple fact of Andy lost his job. I’ve only ever been a mother with a partner who was an academic. I’ve only ever been a homeschooler with a partner as an academic. I’ve only ever been a midwife with a partner who was an academic. I’ve never had three different children doing three different things on any even given day, and had to figure out what and when and how to feed them all before they go, with a baby on my hip, without a partner who has arranged his teaching schedule in a way that let him to answer the question with me. I am an experienced parent, but I have never experienced this. To redefine oneself in one’s mid-forties, after we had — for a brief moment, anyway — built something we thought we could just rest in, is truly humbling. We’ve shifted from “getting to where we were going” to starting all over, with a new baby and a new career. All while watching a genocide unfold in the palms of our hands.

What if I just write, I asked in my last newsletter.

When? About what?

I think about this picture of me, writing this article in the early days of this newsletter, which were just 19 or so months ago but feel like a lifetime, probably because of the 300,000+ lifetimes I’ve witnessed be brutally cut short in the interim. I think about the joy of writing so many of those earlier articles, even though I shouldn’t have had the time to write them, because I had a newborn and 3 other kids and an unemployed husband so I was doing too many births and seeing too many clients for someone just 8 weeks postpartum, but somehow how I wrote them anyway. How good it felt to connect my own personal experiences as a midwife with historical texts and research. Like bringing all the parts of me together. Like a return to my younger, academic self, but better. Last summer, when I had seen far fewer dead children, I had written:

I want all of it, everything, am hungry to create, to be, to experience, to feel my body’s strength. I have endless ambition to do more of what I love, to share more of what I’m good at, to have more of what I want. More more more more. My older children’s births gave me permission to love myself, wholly, with my contradictions, to be who I was and not who I thought I should be; Hanif’s, 15 years later, makes me hungry to integrate all the contradictions and many selves I have become since…It is not surprising that in creating lifeI have re-learned my own fecundity and want to revel in it. I want to be a force because I know I am a force.

Lately I do not feel like a force. I feel instead like a sapling, disjointed and awkward and not sure how I come together, the seams obvious and tentative, my branches visibly bowing under the weight of what they are expected to hold. Not even sure, really, what they are expected to hold. Acorns or leaves, plump juicy peaches, seed pods? I am having growing pains, at forty-five, learning to be a new version of myself as mother, as wife, as midwife, as homeschooler. As writer. My floundering is about time, of course, and the way it slips through my fingers like so much water, lost in the endlessness of nursing and cooking and teaching and seeing clients and attending births and facilitating midwifery groups and filling out birth certificates and walks to the bank or peering at the rice cakes in the grocery store, wondering which flavor might convince my toddler to consume just a few calories when he is so preoccupied during his two-morning-a-week forest school; and also it isn’t about time. It’s about evolving into something new, again, and the strangeness of that. It’s about learning to be me again when I thought — rookie mistake, and one I somehow naively make over and over over and over —I knew who she was. It’s about having a new voice and different things to say than the voice I once had and the things I thought I should say — or perhaps it’d be more accurate to say, the things I thought people wanted to hear — with it. It’s about writing things I love, and immediately wondering if I can do it again, because it’s harder to know what’s next when there’s no expertise to be had in grief and connection the way there is a topic you’ve gotten degrees in. It’s about building up a new foundation on fault lines that haven’t healed, in a world full of fault lines that haven’t healed on which we try to build foundations, in a world that makes clear, every day, how little certain lives — lives that look like my own, but are not my own, because of just a slight bit of luck, the decision of one ancestor to go northeast and not southwest, and nothing more — matter.

Four years ago I wrote an entry about what I called “COVID math:”

I got my hair cut 15 days before we started sheltering in. I keep doing this kind of math. That was 66 days ago, and that Robina had just gotten back from Florida. My sister had asked, before I left, if I would wear a mask on the plane. "Why?" I had replied incredulously.

More math: that conversation was 24 days before sheltering in, and 22 days after the very first time I heard of COVID-19, January 28th, which I remember because I was at a birth. It was the middle of the night, and the laboring person was alternating resting alone and needing our hands and words. Me and the BA and doula sat with her husband in the living room, illuminated only by a screen saver, I think of the ocean. He told us his next door neighbor had been sick "with that new virus from China." I had gotten a chill in that uncanny lighting, my mind going all kinds of dark places, but then quickly read a little about it on my phone and equally quickly concluded I wasn't worried.

I don't feel like that Robina was stupid; that Robina made the best call she could with what little information was available at the time. Actually, that Robina feels less foreign than the Robina who was still hugging friends at the park just 5 days before she sheltered in. There's something about the quick change of consciousness of early March that is especially jarring, that disrupts my sense of self. I guess I can't quite wrap my brain around all the things I wrapped my brain around in the 5, and then 10, and then 15 days, that followed hugging friends in the park. But I still recognize the Robina of 97 days ago who sat at that birth and casually decided she wasn't too afraid of what she then knew of as Corona. She still feels like me. And there's comfort in that, in knowing that this might not be the final after. That I can still relate to some of the befores.

Genocide math: it’s been 359 since I posted this picture of me on a hike I had taken just an hour after Andy told me of the resistance’s October 7th attacks and we looked at each other wide eyed and thought we knew what would happen next and did not know, did not know at all. I still wear that sweatshirt, that yellow hat, that blue carrier. The boots have holes in them now and the jeans are too big. There are parts of this person I don’t recognize, parts of her that have aged so much more than a year, parts of her that have died, even, and also some parts that are better, too. She is not the same person as I am now, and yet I still know her. I still relate to the befores.

Because she left me a trail of breadcrumbs she wrote.

What if I just write?

When? About what?

I guess I’ll find out.

Thank you to reader Jess Marcellus, who commented in my last entry, “f you’re looking for writing topics, I would be curious to hear more about your own experience with this - how you felt with only three children, wanting a fourth but not having one due to time/circumstances, getting pregnant unexpectedly after so much time had passed, and now knowing for sure that your family is complete. Has there been grief around any/all of that for you and how have you navigated it?” This post did not answer all or even most of those questions but it did give me the permission to explore some of the griefs around some of them. And if you’re a reader who is missing the days when I “connect my own personal experiences as a midwife with historical texts and research” I do promise you that one way in which my self now is the same as it ever was is that I have many, many tabs open, hoping to do just that, soon.