The autumn after my now nearly 15 year old son had turned 2, he took to wearing a superman cape everywhere he went. He had been given the cape by two young women having a stoop sale a few blocks from our house, who stood in front of their building wearing bikini tops and cutoff shorts. We were passing by, coming home from some errand or another, possibly manufactured just to get the kids out of the house, as the women were considering the last of their wares and what to do with them. Ilan, who still had not ever consumed any media featuring superheroes but had absorbed — as if from osmosis — their appeal from the culture around him, squeaked as he pointed at the superman symbol he spied on the ground amongst random pieces of jewelry and paperback books. One of the girls, her long blond waves tumbling over her shoulders and her face rosy from the sun, acted faster than I could respond, grabbing the cape and handing it to him. “It’s yours,” she said. “Take it.” “Are you sure?” I asked. “Totally sure,” she smiled. “Can I pay you?” I asked. “No, no, definitely not,” she waved us away. Ilan was thrilled.

The cape was unlike any Superman costume I’d seen before or have seen since, and I still find it hard to describe. It was not simply a cape that tied around one’s neck — though it did, of course, incorporate one — but a stretchy polyester vest that covered both the chest and back of the person who wore it. There were no sides to the vest, and it tied with a sash around the waist. The open sides made me wonder at its original purpose and how it had been (or not been) coordinated into a larger costume. It was also, decidedly, sized for an adult woman. But Illy loved it, and from that day on wore it over his clothes pretty much every day, for months.

I loved it, too. There was something about walking around with a small, cherubic child wearing a cape long enough to almost trip him everywhere he went that meant we were the recipients of the best kind of human attention. Truck drivers would lean out their windows and delightedly call out, “Hey, Superman!” Every person we passed smiled and waved. Small considerations, like letting me go first in a line at a store, were more common, and usually accompanied by some quip about how Superman needed to go about his business saving lives.

All of this attention should have dissuaded Ilan from wearing it. He was, after all, my shyest kid, my child who would sometimes stand in the hallway of any gathering that involved my loud, large Pakistani family for infuriatingly long times, afraid to step into the noise and fray. He was cautious, sensitive. And yet he walked around like a celebrity about town in that cape, receiving the attention with a grin, his huge eyes wide and delighted by the improbability that anyone would mistake his tiny body for that of a superhero’s, would believe that he was someone who could keep everyone else safe. I do wonder if it was that sense of safety that made him wear it; that somehow, playacting as a superhero gave him a sense of security he didn’t usually feel, even as it brought attention upon him that usually intimidated him.

Truth be told, it made me feel safe, too. I’ve never felt as secure in my neighborhood as I did walking around with Superman at my side, knowing we would all pretend together. Knowing everyone around me was enraptured by the tender imagination of childhood. Knowing we all agreed it was worth protecting.

Now I live in a world where we know what it looks for a man to cradle the head of his decapitated toddler and some us not only look the other way but justify it.

*****

Just over a year ago, I wrote, “I didn’t start a newsletter to write about genocide, or what it does to those of us witnessing one in real time.” But, I continued rhetorically, how can you write about anything but genocide during a genocide? It is a year later, and I still have the same questions, only amplified. I didn’t start a newsletter to write about genocide or the United States’ accelerated slide into fascism. I didn’t start a newsletter to quickly and breathlessly provide my take on the dismantling of a government, or McCarthy-era-style kidnappings. I did not start a newsletter to write about the stock market. I started a newsletter, and here I’ll quote myself again, “to write about what I have the most to offer about — growing, birthing, and nurturing our children, the oppressive systems and institutions that surround those processes and attempt to strangle them out of their liberatory potential, and all the ways we can reclaim it.” Even though I know that, in actuality, writing about those things is as important — if not more important, because they remain our foundations even in systemic collapse — as it ever was, it all feels so comparatively small, so insignificant, so lacking in urgency.

When I was prepping to teach Martyr! (by far my favorite read not only of this year, but in some time; please pick it up if you haven’t already) earlier this semester, I found myself reading interviews with Kaveh Akbar, and I felt a small hot spark of recognition in his answers in one of them, something I don’t always feel when reading about how other authors describe writing.

Why do you write?

I love it. Being an addict in recovery, I’ve lost my privileges to all my favorite highs. I’m not allowed to do any of my favorite drugs anymore, but writing is the only exception. I can get high as shit off writing. It sounds corny, but for real — If I write in the morning, all day I’ll be walking around like I’m floating…

In that same analogy — writing as almost a replacement drug — what does writer’s block feel like for you?

I’ve never experienced it.

Woah. Really?

I mean, I have project block — sometimes I can’t finish this essay, or I can’t finish this particular thing — but writing is just sticking words to each other. Nobody says that they have Lego block; these are my materials and I’m just playing with them.

I’ve never experienced it, either. I’ve been blocked from writing by the constraints of my life, sure, but there has never been a time where my brain does not crave to write, and when given the opportunity, cannot begin. If given the time to write, I will write. I just will. I’ve never not. Even in the moments where I’ve sat down anticipating that I won’t be able to, I have. I just start picking up the blocks and clicking them together. Sometimes — really most of the time: I’m a prolific writer but I’m an even more obsessive rewriter — the form those blocks will take isn’t quite right, and I will need to rearrange them later, but I can always begin building. Nor am I a slow writer; I write prolifically, relatively quickly (you might remember here how this summer I wrote AND edited 153 pages of my book in the equivalent of two forty-hour work weeks).

But I didn’t become a journalist for a reason. I don’t write slowly, but I write about slow things. I don’t want to churn out content about Breaking! News! And yet I also find it hard to imagine putting any writing out into the world right now that isn’t a response to all that is being broken. The instagram-ification of Substack isn’t helping with that, of course, nor is the fact that I do have limited time to write and most of it is, as I shared in a note recently, being devoted to the book project.

But some of it is also that I cannot help but find myself wondering if there’s still even a place for my writing in the world as it is currently being restructured. I mean this in both the do I have anything worthwhile to say to people in polycrisis? way and also in the will the publishing industry even be able to publish books like mine? way. As I slowly and arduously approach the finish line of the book proposal I’ve been writing and rewriting over the last four and a half years, it occurs to me that four and a half years ago I had never, not for one minute, thought there was a chance it would not be published because it was controversial in any way. Any of my doubts were about my own self-worth as an artist, or the ability of the publishing industry to see me as sufficiently capable of making them money. Now, I live in a world where people are being kidnapped for writing simple college newspaper articles about a genocide we are all witnessing in real time, and it would be naive to not consider what that means for all of our futures. (Though I hope it need not be said that what is happening to Rümeysa Öztürk is worth caring about regardless of what it portends for the rest of us, because she is a human being, and human beings should not be stolen and held hostage in cells without the medicine they need to survive.)

A couple of weeks ago in High School homeschool lit class, we read Audre Lorde’s essay “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” I assigned it because we were also reading the short story collection Fairy Tales for Lost Children by the Somali-British author Diriye Osman, and he refers Lorde’s speech more than once. The teens and I sat around the table with cups of steaming chai and I delightedly listened to them deconstruct phrases like “we fear the visibility without which we cannot truly live,” phrases I had also deconstructed as a teen. When I first came across Audre Lorde then, in the late nineties, “intersectionality” was not a term I had yet learned - I wouldn’t, actually, encounter Kimberlé Crenshaw until graduate school, and so my nascent understanding of her work was intimate rather than structural. In particular, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” which I now understand as much as an indictment against the structures that silence — and those who comply with that silencing — as it is a clarion call for people to speak their own truths, mostly captivated me as a teen for its the framing of silence as a kind of cancer that can destroy oneself from the inside out. As a teenager growing up long before the #metoo movement was even a dream, internalized shame had kept me silent about my own history of sexual violence, and I turned the phrase “your silence will not protect you” around and around in my mouth like a smooth, tart hard candy. It was compelling, but it also made my mouth pucker. To me, my silence was protecting me, controlling what people thought of me. But it was also threatening to devour me whole, not only because I was haunted by unacknowledged trauma that overdetermined so much of how I moved through the world, my relationships, and my own sense of self, but because, literally, my insides were devouring themselves; I refused to feed them much else. The discipline I subjected on the body I felt had betrayed me was its own form of self-silencing, an attempt to keep myself tiny, acceptable, and so untethered I could possibly disappear, light enough to be carried off on the wind. The idea that silence was something to be resisted, the idea that it would be liberating to make myself and my pain visible, was a revolution, and it would be many years before I even tried.

It was strange to return to this speech in 2025, and read, “Your silence will not protect you,” only to find myself thinking of Rümeysa Öztürk or Mahmoud Khalil, and surprise myself with the wonder, “but won’t it?”

Being silent nearly killed me, and yet.

*****

One of the birthgivers I write about in my book is someone I cared for when I was doing my residency in midwifery school, a woman for whom I use the pseudonym “Rana.” Rana was a refugee of the Syrian Civil War, though I never learned much about her journey or how she managed to get to NYC when most fleeing Syria at the time found themselves in overcrowded, under-resourced refugee camps in Greece or Turkey. She was always accompanied by her aunt, who had emigrated many decades earlier, and always declined my offers of an official translator, choosing her aunt to translate for her instead. There wasn’t, in truth, much to translate. Rana was always evasive, demurely answering “Alla hu Akhbar,” a phrase for which I needed no translation, and lifting her eyes at the ceiling, whenever I asked her any questions about Syria, or her husband who was still in Jordan, or how she liked New York, or, really, anything at all. Her Aunt would roll her eyes often in response to this, and tell me, “she still thinks the walls have ears; she grew up in Syria, you know” as though Rana’s affect were not a reasonable response to having resided in a country whose government made people disappear for the slightest perceived disloyalty for decades even before the war. I’ve thought about Rana and her aunt, and the phrase “the walls have ears” frequently in the years since, but especially now I find myself often returning to the way her aunt nudged me as if we were sophisticates, cosmopolitans who would never have to worry about such things, as if such fear were beneath us, as if living in a place where you would be punished for your political views and allegiances was as remote a possibility as us living on Mars.

In my middle grade lit class, we recently read The Lost Year , a book about the Holodmor, or manufactured famine by the Soviets in the Ukraine in the 1930s, and a major theme in the novel is people being sent to work camps, or simply executed, for speaking against “Papa Stalin.” A major theme, too, is the way in which Walter Duranty — the lead American reporter covering the Soviet Union for the New York Times — simply regurgitated Soviet propaganda in order to maintain his proximity to power, denying not only the famine but many other of Stalin’s atrocities. It portrays ordinary people speaking up and fighting these narratives, of telling their own stories despite suppression, as heroes. The book is, in its own way, a middle grade version of the idea that our silences do not protect us.

But it, like most narratives about the United States, isn’t writing about a United States where a young immigrant from an “undesirable” country, writing letters to expose U.S. complicity in a famine that was killing millions of people might realistically be sent to a detention center in Louisiana as a result.

Is the fact that this is happening now supposed to make us feel safer? Does anyone buy into the farce that these students constitute a threat? What kind of person would you have to be to watch the video of Öztürk being abducted by masked kidnappers in broad daylight and find your body filling with a warm sense of relaxation and ease? I find it hard to believe a single person could ever watch this video of ICE breaking the car window of a mother and forcibly removing her, in front of her children, and feel safer. “You can’t take her just because you want to,” her daughter screams. And yet. They are. Trump says “homegrowns” are next. Is this safety? Does it make people feel secure to think there are people around us who choose to behave this way, who choose to enact these kinds of violences? These actions are the natural consequence of the oppressive systems our country is founded upon, one might argue. Perhaps. But systems don’t kidnap, disappear, and traffic humans. Other humans do. Human beings make the systems; the system is made of human beings. Human bodies, human voices, human wills, human imaginations. “We’re not monsters” one of the ICE “agents” who helped transport Öztürk said to her. But knowing that his is a version of humanity that exists in the world is not something that helps me sleep at night.

In all the conversations about detention and deportation and criminalisation of dissent that are happening right now, I’ve noticed that one of the foundational conceits that never seems to be questioned is this idea that “strong borders” are a form of security. While people may disagree on the way that they are enforced, few seem to question the idea that they should exist in the first place. But it seems to me that there’s a case to be made that it is, in fact, the very idea of borders, the need for them to be delineated and constantly maintained, that make us less safe to begin with.

*****

Earlier this month, in the span of a week, I cared for four different people in labor. One of them experienced what is known as pROM, or premature rupture of membranes. As I’ve written about a bit before, most of my clients choose to “expectantly manage” pROM, which means waiting, sometimes interminably long times, for labor to start. This is an approach that is supported by evidence (a good resource for consumers on this is here), but it is very much not the norm among the western Medical Industrial Complex, who regularly induce such labors at 12 or 24 hours — which is to say, a majority of labors involving pROM because in my experience, most people do not go into their own labor that quickly if they are truly experiencing pROM, or membrane rupture without any labor, rather than water that has broken in an as-of-yet unrecognized early labor. When my clients experience pROM, we check in every day and listen to their baby’s heartrate and take vitals while we we wait for labor to start; at one of these visits earlier in the month, another client, who was waiting outside the office for her visit to begin, asked if she could interrupt our visit to use the office bathroom — she was, after all, 40 weeks pregnant. As it so happened, she was also someone who had experienced pROM in her first labor.

When she walked through the office, the person experiencing pROM now asked, “any words of wisdom?”

“It’s going to be okay,” the second responded. “Trust your baby, and your body. And trust Robina. Labor will come.”

She was right.

Supporting people who are experiencing pROM is, to me, one of the biggest exercises in both facilitating and embodying faith in a calling that is actually, at root, all about facilitating and embodying faith. I profoundly trust in these cases — and profoundly trust that trying to force contractions often does more harm than good — in a culture that is insistent we must force the body to comply with our timelines. In a culture that believes the body to be a risk to itself that must be managed, no matter what harms come from that management. The amounts of time that I reliably wait for labor to start would almost certainly be called Very Dangerous by many providers within the MIC, even though the main risk when it comes to pROM is infection, and the main risk for infection is vaginal exams, something I do not perform at all in these labors. In fact, there’s actually very little evidence to suggest that infection is a strong risk in the setting of pROM without vaginal exams — both because the evidence we have suggests it simply isn’t, but also because robust evidence simply doesn’t exist; only 3 out of thirty-odd studies on PROM even consider people who have not had vaginal exams. This is though it’s been well established that frequency of vaginal exams is the single largest factor that increases the risk of infection: 3-4 vaginal exams double the odds from having “less than 3” (note that the control is not zero, or having no vaginal exams at all), while having 8 or more makes it 5 times as likely. And yet the very first thing many providers do when someone is admitted with pROM, even if they are standing there looking at a person who is obviously and clearly Very Much Not In Labor, is perform a vaginal exam as a “baseline.” It gives them no usable information, and is entirely unnecessary. It does nothing but start the clock on infection risk. And yet.

Supposedly, this is the safer way to deal with pROM: to do the very thing that makes it “risky” in the first place.

During the week where I took care of this client and three others, I helped fill birth pools by hand and raced up the FDR in dusky light and helped older siblings with bags of freeze-dried mango and answered when they asked why their mother sounded “sad.” I listened to baby’s heart rates when they were inside their mothers’ bodies, being oxygenated by their mothers’ bodies, then listened to them once they were outside and had begun breathing for themselves. When one of them came out limp and pale and stunned, I paused and took him in, asking whether he needed my help, before gently holding him like a football, hovering just over his mother’s skin, to help him clear his lungs of fluid. He coughed, then cried, and I returned him to where he belonged. I weighed and measured and waited and made small talk. I, also, celebrated my third child’s birthday, hosted 40-odd members of my family for Eid, and grieved the unexpected loss of my Aunt Ellen.

My aunt was unusually petite, a little sprite of a person who bubbled effervescently. Improbably, three out of those four babies who entered the world the week she departed were uncharacteristically little girls, two of them just barely 6 pounds. Synchronicities like this are where I find my sense of safety in the universe.

*****

In many ways, the book I’m writing is at root about safety: how the concept is weaponized in order to justify harm; how we reclaim and build for each other safety in the face of violence and trauma; how it is often found, paradoxically, in vulnerability; and, importantly, how binaries like “safe” and “unsafe” are figments of our imagination in the first place, constructions that never exist purely in opposition to each other.

When I sit around the table with my high school homeschoolers, all of us teary-eyed when we discuss the way in which postcolonial authors talk about intergenerational wounds and the capacity to heal them, or when I watch their neurons firing rapidly, as they finish each other’s sentences about W.E.B. Du Bois’ understanding of “double consciousness” in relationship to the concept of the colonial gaze, I feel as secure and at ease as I ever have. It occurred to me, sitting around the table with them a few days after I published my last, I-guess-we-can-call-it-viral-because-the-IG-version-had-almost-a-million-views-(wtf) essay about building community: I had not, not explicitly, mentioned these teenagers in it. But they are, in fact, an integral part of mine. They are who I’ve spent my days with over decades. They are who I’ve grown with in parallel — them from babies into children and teens; me from new mother into mother of four, from academic to midwife — and they have taught me as much as any of my peers. I would trust them to hide me from the Gestapo as much as I’d trust any of the adults I know (if not more than many I know), and it is no exaggeration to say I would lay down my life to protect theirs’. They are, in fact, part of why I homeschooled in the first place; because I wanted my life to be one of intergenerational community, not one where people are segregated according to age but intertwined, all the time. I wanted to build a world that was imprinted as much as it could be by walking with Superman, seeing the world he made possible. Who wouldn’t?

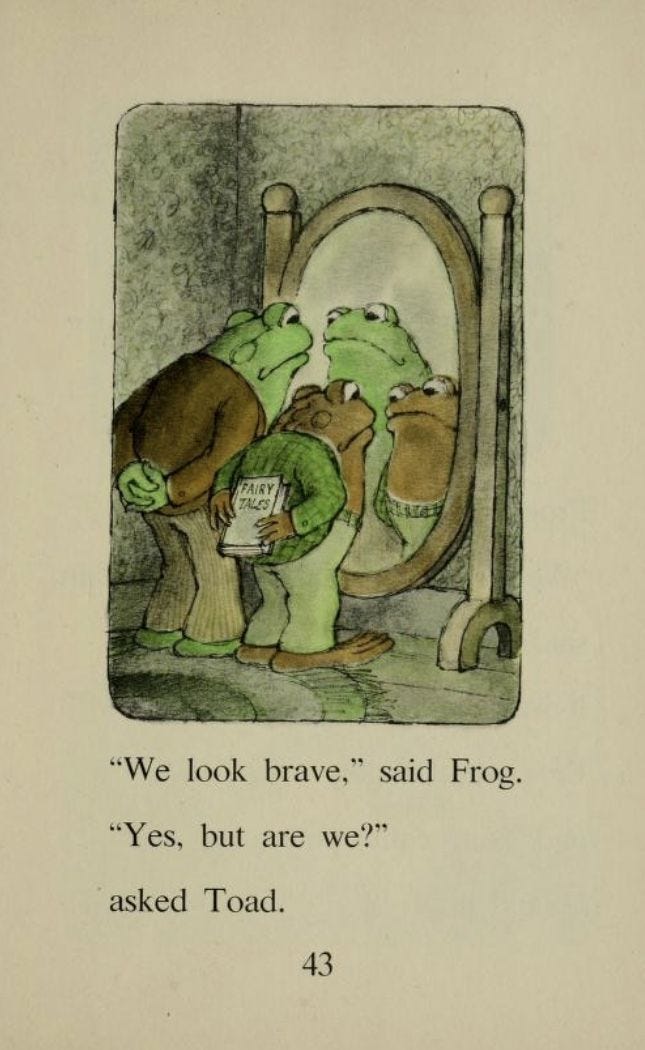

When I was a fresh-out-of-college editorial assistant at a children’s publishing house, one of my tasks, along with all the other young-and-underpaid staff of said publishing house, was to periodically stay past 5 to sort through all the fan-mail we had received from children and respond to them, an activity for which we were paid overtime. It is so strange to me, in retrospect, that a giant corporation would devote any resources at all to such a thing, and yet they did. My favorite was to open the envelopes addressed to Frog and Toad and to try to write back in a voice that sounded like them rather than simply fold up and mail back the xeroxed canned response we were given.

When I think back to all the hours I spent in the windowless offices and conference rooms in the year I worked at that job, I remember very little of the actual work. It’’s a sea of hazy memories, of stark fluorescent lights and photocopiers and being so bored I could barely stay awake some days. I vaguely remember interactions with the guy in the food cart from whom I got my morning coffee, and how surreal it was to have a guy in the food cart from whom I got my morning coffee. But besides the fact that I was there, at only my second day of work ever, on the morning of 9/11, and that — I swear this is true even though it sounds like a bad novel — my boss told us the best thing we could do under the circumstances was focus on our work, my only truly distinct memories are of being Frog. Of being Toad. I wasn’t condescending to the kids who believed they were writing to characters in a picture book. The world they lived in, it seemed to me, was no more imaginary or irrational than the corporate world I found myself. I valued it as much, if not more, than that one, and I wanted to protect it.

I never did have even the slightest hope of responding personally to all the letters; there were just too many. Eventually, as the clock started to wind down, I’d start stuffing envelopes with the canned response and the little keychains that we were meant to send along with them. But there are a handful of children in this world, who are now grown-ups, who at some point in their lives received a letter from me, barely more than a child myself, writing them back as though the characters they loved were real. And they were, because I was.

There are so many things we can think of when we think of safety, and that is one of mine.

Love,

Toad

I know it’s mid-April, dear readers, but I did want to share my March playlist! The first of March coincided with the first day of Ramadan this year, and my aunt passed at the end of the month, so the feel of the playlist is heavily inspired by both of those portals, by the sense of what is normal being interrupted and turned on its head, and also, by the sense of us being stripped down to our most essential. I hope it grants you some of the comfort and inspiration it has me.

And if you happened to miss my January and February playlists, they are here and here. I’ve been very much enjoying making these each month, and hope to both keep up this practice, and to keep offering it to you; do let me know if you are enjoying them.

I don't know if I can comment anything that will do justice to what this piece made me feel and think. But I just wanted to thank you. This is so dense with meaning and beauty and meeting-the-moment. Thank you.

Really relate to the “what am I writing about if not the polycrisis” and “is it even helping/does it matter” feelings ❤️🩹