Blood between the floorboards

How to become a person of place in a place that's always changing?

Earlier this week, I was walking home from the train with Josie and Hanif after our homeschool coop toured the Henry Street Settlement House, and we ran into our mailman, Walter. It was a glorious spring day, bright and clear and warm, and Hanif was asleep in the stroller. Josie perched on the fence surrounding a tree bed on the street. Walter and I talked about parking.

If you don’t already know, this is not an unusual topic of conversations among New Yorkers: there are relatively few places to live in NYC where you won’t, if you have a car, spend an inordinate amount of your precious brain space on finding someplace to put your car when you are not using it, or strategizing how to avoid using your car when you know you will not be able to find somewhere to put it either when you return. My heavily gentrified neighborhood is now particularly bad in this regard. But once upon a time, people would just…park. Usually they would even find spots in front of their own houses and not blocks away. Walter, who has been our mailman for almost as long as I’ve lived on this block1 remembered that time.

Walter and I weren’t really talking about parking, though. We were talking about the seemingly endless development specifically on my block, and in my neighborhood generally. Currently, right across the street from me, they are building 40 luxury condos in a space where a churchyard with 200 year old trees used to be. Two houses down from that, they are knocking down yet another of the roughly one hundred year old houses on our block to build another building of condos that look like they were constructed by a middle schooler in Minecraft. Much like the ones they’re building where the Grand Prospect Hall used to be, or the one that now exists where Eagle Provisions once did. Simple boxes with huge windows. Maybe some balconies, or maybe not. Probably gray. Sharp angles and efficient modernity. The botox of architecture, expressionless and the same.

My house was built in 1910. In the years between 1910 and when I moved in in 2001, a series of additions were attached to it with what appears to be Elmer’s glue and popsicle sticks by the assorted Italian families that once lived in it. There are no gleaming lines and reassuringly efficient angles. The floor plan is decidedly weird, thanks to all of these additions: something like an L, or maybe more like an uneven U? The seams where the additions were connected tend to spring leaks even though we’ve repaired the roof too many times to count. When we renovated our basement to make room for my home office, the architect pointed out that the walls had been finished by someone pressing a door into the concrete again and again, sideways, and even now, even with those indentations covered by sheet rock, I think about the wall of sideways entrances nearly daily. The architect later tapped and walked slowly around an enormous, uneven column in the middle of our basement, a befuddled look on his face. It was not in a location that made sense from a structural perspective, he told us. “I can’t quite figure what this thing is doing,” he finally said, “but we are absolutely not going to try to find out.” We would build around it, continuing with the tradition of odd, inscrutable shapes.

I don’t know the story behind the column or its even larger base of assorted, haphazard seeming bricks. I don't know who all the additions made room for, or who made all the indentations on the wall. I do know that beyond all my frustrations with these idiosyncrasies, I have an attachment to their mysteries, a sort of incalculable pull towards the people I don’t know who left their residues in this place that now houses my own most intimate moments. My own babies were born here. Possibly — probably, in fact, since most births in 1910 in New York City were still happening at home — others were too. In what sounds like a story from a horror movie, after my third birth and before we finished the basement, I dripped a small bit of blood down my leg and onto the floorboards when I arose from bed for the first time, and Andy, a few days later, found a drop of it in his basement office. We had laughed at this gruesomeness and joked about how of course this would happen in our old house, but I think about it often, wondering what cells still live beneath my floor. Whose cells. My house feels like an alive thing to me. It is both comforting and terrifying that my family might be the only thing tethering its life to this place, that it seems almost inevitable that, were we to leave, every story held within it would surely be knocked down and disappear.

****

Recently, one of my clients asked me what people typically do with their placentas after birth. Unsurprisingly, she was mostly interested in how often people ate it or encapsulated it into pills. “What happens to the placenta if people don’t consume it?” she asked.

“Well, ” I answered, “I think it often ends up buried, or even more often, sitting in people’s freezers waiting to be buried. Otherwise, we just get rid of it.”

“People bury it?” she asked. “Where?”

I told her the stories then: sometimes people had a yard. Sometimes they brought it to their childhood homes. Other people had second homes upstate or out of the city. One couple brought it to the site of an outdoor music festival that held emotional significance for them, and buried it there. More than one had found a corner of Prospect Park to bury it in, undetected by cops. I took care of another couple who had given birth for the first time in the Netherlands, and they had also buried it in a public park there. Once, a client asked if she could throw it into the East River.

“I never found out if she did,” I mused.

The client found all of these stories hilarious; it had never occurred to her that one might bury a placenta. “We’ll just throw ours out,” she said. But the truth is that treating the placenta as medical waste is actually the outlier perspective. Most cultures for centuries have believed the handling of the afterbirth was sacred and attached to the overall future well-being of both birthgiver and baby. In 2010, medical anthropologists Daniel Benyshek and Sharon Young studied placental traditions across 179 societies; among the 109 communities demonstrating ritual around the disposal of the placenta, they counted 169 different disposal methods, including incineration, consumption, hanging, and drying but most frequently burying.2 Placental burial was and is often thought to link a soul to the earth, ancestors, or both; the indigenous Hawaiian, Navajo, and Māori, for example, believe burying the placenta binds the child to that land and, therefore, their ancestral heritage.3 In fact, in Māori the word for land is placenta: “whenua” means both.

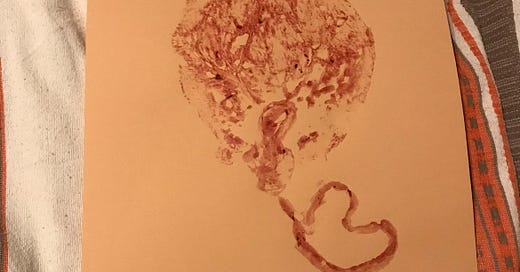

After birth, when I am taking people on a tour of their own placentas, showing them the hole in the membranes that reveals to us where the waters released, or how large this shared organ is (and, therefore, how large the space whose open vessels their uterus is trying to compress now that the placenta has released), I show them why people often refer to the baby’s side of the placenta as the tree of life. “People see this as the trunk, and these as the branches,” I will point out. “But,” I will say, flipping the placenta inside out to show how the birthgiver side attaches to the uterine wall, and how the membranes stretch to hold the baby and the amniotic fluid, “the more I look at placentas the more they resemble to me a whole universe. I can almost imagine them as the baby’s night sky alight, a mystery they gaze into from their little sea.” And I do. I can see how those vessels, pulsing with life, flowing with the air the babies do not have to breathe themselves and yet are still oxygenated by, might sparkle like stars, might whistle in like a myth of things they have yet to know.

****

When I was a new mother in my late twenties and early thirties, I felt like I was constantly reading what I came to think of “Dear John” letters. These weren’t to partners, but to the city in which I lived, and were penned by bloggers (many of whom had built a readership because of living and parenting in New York), acquaintances, colleagues, and, occasionally, friends. All followed a similar form. They began by waxing nostalgic, thanking the city for all its good times, for being the location of so many youthful foibles and lessons. “But,” the conclusion always seemed to be “it’s not me, it’s you.” New York City, they would say, was not a place to live longterm, not a place to raise a family. It was too much: too congested, too loud, too expensive, too stressful, too busy, too trafficky, too inconvenient, too smelly, too depressing, too hard.

Now, I want to be clear at the outset here: New York is all of those things. It is an indubitably difficult place to live, in countless ways, and despite the recent study that claims New York City is the happiest city in the U.S. (and 17th in the world, the only U.S. city anywhere in the top 25; Minneapolis is number 30). I do not begrudge anyone, not then and certainly not now, for not wanting to live here. Hell, sometimes I don’t want to live here myself (see: every single morning at 7:00 on the dot, when my house begins shaking and becomes filled with the beeping and rumbling of construction vehicles due to the aforementioned 40 luxury condo project across the street).

Still, the letters physically pained me to read. Even as I understood rationally why they were written, they filled me with an irrational, bereft sort of rage. It wasn’t the leaving. It was the tone. It was the way they read like an overdetermined performance; a disattached, removed convention. It was the way each letter presented its conclusions as obvious: New York City was a place for young, careless people, not a serious place where one could raise a family, not a place anyone would ever put down roots.

To someone who had been raised in New York, to someone who had deep roots in and attachment to this city and was raising a family there herself, this was not such an obvious conclusion. What was actually obvious, to me, was that these letters rested on a narrative of erasure. Each one obscured, as if pressing repeatedly on its backspace key during their composition, the many families who had in fact put down roots in the city. Even more importantly, they elided the fact that it was often the letters writers themselves who had played a role in displacing those families, in driving up prices and changing the cultural and racial backgrounds of the neighborhoods where those families had lived. I knew the letter writers were probably surrounded by plenty of families raising children in New York; it’s just they had escaped noticed because they weren’t white and didn’t conform to the platonic ideal many Americans have to what putting down roots as a family should look like. To those letter writers, having 30 people live in a tiny little row house in Brooklyn, as my Pakistani family had, was unimaginable. I had understood this intimately, had been a child during a time when the (mostly ethnic) white families around me moved to the suburbs, had come into adulthood during a time when young white people started displacing the brown families who had remained. I watched as the old timers who sat on their porches and chatted with neighbors passed away and their houses were razed and replaced by apartment complexes most of the people who once lived in my neighborhood could no longer afford. The doors of these new buildings revolved with young people who stepped over me and my children as we drew with chalk on the sidewalk, and I made a game of guessing who would acknowledge us as they walked past, and who wouldn’t. I was rarely wrong. It was obvious, to whom we were invisible, just part of the backdrop.

It wasn’t the revolving door that grieved me so much as the sense that, for many, the city wasn’t a living, breathing organism with whom they were in intimate relationship while the door wasn’t revolving. It was the sense that the city comprised simple scenery, the setting for young Main Character Moments that could, once it had served that purpose, be discarded in search of the next backdrop. This was, it seemed to me, not the way we were meant to relate the spaces in which we lived — places with deep histories and ecosystems, places of real people and genealogies, places where things had died and survived. We were meant to have a sense of place, and to feel our place within it. We were meant to feel a sense of investment in where we lived, to be curious about what it meant not just to us right now in this one moment, but to the people around us and to the people who had come before. We were meant to discover where our cells fit in in those deep histories and ecosystems and genealogies, to notice not just how we were being changed by the space around us but how we were changing it ourselves. We were meant to notice the holy miracle of the dirt in our tiny backyards or community gardens or playgrounds, the little dandelions and huge old trees that grew in that dirt and peeked through the cracks in the sidewalk or broke its concrete with their huge roots, the smell of rain on that concrete, the way the rain became waterways, and the way those waterways held histories and possibilities and violences and cooperations and migrations and deep dark animal worlds. None of that was backdrop to me. It was integral to me. It was, in fact, me.

I understood why the city didn’t feel like a place to put down roots for many people. But also, I couldn’t help wondering, was any place? Many of the people who were leaving New York weren’t going back to the places they were connected to in any real way. Few were moving back to where they had been raised. Most were simply following jobs, or calculating various data points about other places in the hopes that they would find what they were looking for. Many would move again. And again. Behind the remove with which they talked about the city, behind the breezy nonchalance, I could hear it: we had lost our connection to place. We called it freedom, but it was severance. As a culture, we were floating, untethered, our cords cut, and calling it a choice. We were imagining place as scenery, as static in the background, rather than a living organism that we were part of and that was a part of us.

Global capital relies on this severance. Industrialization has relied on us being untethered. When we are unattached to our homes, our roots, the communities around us, the earth beneath our feet, we are vulnerable. When we are in extractive relationship with the places we live, we are in a better position to be extracted from.

Art critic John Berger wrote “Today, as soon as very early childhood is over, the house can never again be home, as it was in other epochs. This century, for all its wealth and with all its communication systems, is the century of banishment.”

Banishment, but we were calling it mobility.

****

Recently in postcolonial lit class, we read poetry, and one of the pieces was “Postcolonial Love Poem” by Mojave and Latinx poet Natalie Diaz. We talked mostly of the way Diaz writes about land with intimacy, the way she imagines intimacy as land. Wren pointed out that the way Diaz begins the poem — “I’ve been taught bloodstones can cure a snakebite, / can stop the bleeding—most people forgot this / when the war ended” — sets up a the outset that the reader will spend the entirety of the poem confronted by all they don’t know. Diaz presents indigenous and colonial imaginings in opposition and also in union, destabilizing any easy binaries and with it our very footing. It pulses with all we have lost, and also, all that is still alive, in the gems and plant life and canons of our bodies and the way we use to them to “wage love and worse.” We are the snake and the snakebite and we hold and also have forgotten the cure.

Earlier that same week, when our homeschool coop visited the Henry Street Settlement House, before I talked to Walter about parking, our tour guide asked the children what they knew about migration. We had laughed: more of the families in the group are intimately acquainted with it than not; a family where both parents are not immigrants or first generation is the tiny minority. In an earlier meetup with the group, we had found ourselves in one of those seemingly inevitable “Is it time to leave the United States?” conversations that are so frequent these days both online and in person, and one of the American parents talked about trying to get their German citizenship to flee. “It’s not that easy, though,” I said, “to be an immigrant.” My friend Angelica, who emigrated from Spain when her first two children were little, agreed. And then she said, “it’s not even that easy to return.”

“You are reminding me,” I told Angelica then, “of this one little conversation in a book I read as a teenager that always resonated so deeply for me.” And then I quoted it, because that’s how many times I have thought of this passage of Maximum City by Suketu Mehta:

My father once, in New York, exasperated by my relentless demands to be sent back to finish high school in Bombay, shouted at me, “when you went there, you wanted to come here. Now that you're here, you want to go back.”

It was when I first realized I had a new nationality: citizen of the country of longing.

At the Henry Street Settlement that day, we citizens of the country of longing all sat on the floor of its entry way and watched a video about its history (which you can also watch, here; if you’re not familiar with the settlement house movement, you can get a little background on that here). The Henry Street Settlement was borne, as it turns out, of a birth. Lillian Wald, a 26 year old nurse, was teaching a homemaking class to a group of immigrant women on the Lower East Side when she was summoned to a tenement where a woman lay dying of a postpartum hemorrhage after being abandoned by her doctor because of her inability to pay. “The misery in the room and the walk through the gritty streets,” the video narrator told us, was a “baptism by fire.” It didn’t surprise me. Birth is a portal that way. (The hemorrhaging woman, by the way, survived.)

“The thing is,” Angelica leaned over to whisper to me as we watched all the other ways the Henry Street Settlement went about its work trying to not only provide health care but address the social determinants of health, “it’s the descendants of these immigrants who came over without any process and were living in these conditions who are now yelling about building walls and getting ‘illegals’ out of the country.”

“That is exactly what I was thinking!” I exclaimed. And it was (alongside a vague wonder about whether Lillian Wald was one of the public health nurses who basically eradicated Black, indigenous, and ethnic white midwifery out of existence).

We are the snake and the snakebite and we hold and have forgotten the cure. When the inevitable conversations about leaving this city or this country come up, I understand them. But there is a defiant rage in me, a part that does not want to cede this place to people who would only extract from it. That refuses to be banished.

I want to be careful here to point out that to have roots someplace is not the same thing as to have ownership over it. I am not indigenous to this land, and I do not think it is hyperbolic to say that the future of our planet probably depends on land back movements. Whatever roots I do have here are borne of the simple improbability that I exist at all, that the waterways made this place what it is and my father could fly the 7000 miles between Lahore and New York City to fall in love with a woman whose grandparents had sailed the 45000 miles between Naples and Sicily and New York City. Whatever roots I have here are a tangle that weave and tunnel underneath oceans. But still they exist and exert a pull. It is a pull that still bleeds every time an old tree is severed from its roots to make way for condos that will not last as long as the tree had.

“The way Diaz describes bodies,” Wren said in postcolonial lit class, “is in a landscape unfamiliar to me.” I had wondered, then: what sort of landscape of the body would feel familiar to this daughter of mine? What poem would she write? I have intentionally tried to instill a sense of place in my children, have dug my hands in the dirt and buried their placentas here, have read to them about this place’s History and also all the stories that came before History or have been precluded by History. I have taken them to ancient glacial rocks and waterways and hiked in search of spring ephemerals. I wanted to foster a relationship of intimacy with the place around them because I could not imagine a sense of health coming without it. How do you feel whole without seeing yourself as part of a whole? But I do not know in what language they feel that intimacy or, even, if they do at all. They are, after all, children still, and live in a world of possibility rather than groundedness. They also are growing up in a very different New York than I had, one that is razed and rebuilt with rapidity. How do you become a person of place in a place that is always changing? I barely know the answer to that question myself.

Here is what I do know. I once wrote something like, I know the streets of my neighborhood like the lines on my palm when writing about the devastation in Gaza and how losing place is a casualty we often gloss over when we, understandably, focus on death tolls. But the truth is, I actually know the streets of my neighborhood better than my own palm. If you were to show me the cartography of my own hand, I would never recognize it as easily as I would the street map of this place where I have loved and cried and birthed and grieved and laughed and hoped to die and lived anyway. This place where my cells have become part of the floorboards. I know that for sure.

Comrades, I am delayed in sharing my April playlist, but here it is, better late than never, and now that I’ve finished my book proposal (!!) I’m hopeful to be able to post here more frequently than I have been, and will have the May one up for you soon enough!

The exact number I’ve lived on this block is nearly 24 years, but I grew up a block away, and before that lived 8 blocks away, so I’ve been in this neighborhood a minute, which is to say all 45 years of my life.

Young SM, and Benyshek DC. “In search of human placentophagy: a cross-cultural survey of human placenta consumption, disposal practices, and cultural beliefs.” Ecol Food Nutr. 2010; 49(6):467-84.

Moeti C, Mulaudzi FM, Rasweswe MM. The Disposal of Placenta among Indigenous Groups Globally: An Integrative Literature Review. Int J Reprod Med. 2023 Oct 26;2023:6676809. doi: 10.1155/2023/6676809. PMID: 37927303; PMCID: PMC10622600.

This was really beautiful, thank you. 💕

This is so good! I don’t know how to describe what I’m feeling after finishing it just now. Yearning for something I don’t have. Hoping that your efforts and your intentions pay off for your children. Thank you so much, excellent work!