Come for the Super Mario Brothers, Stay for the Kropotkin: A Love Story

(and other disparate thoughts on mutuality)

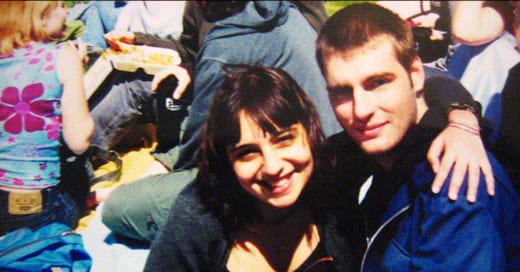

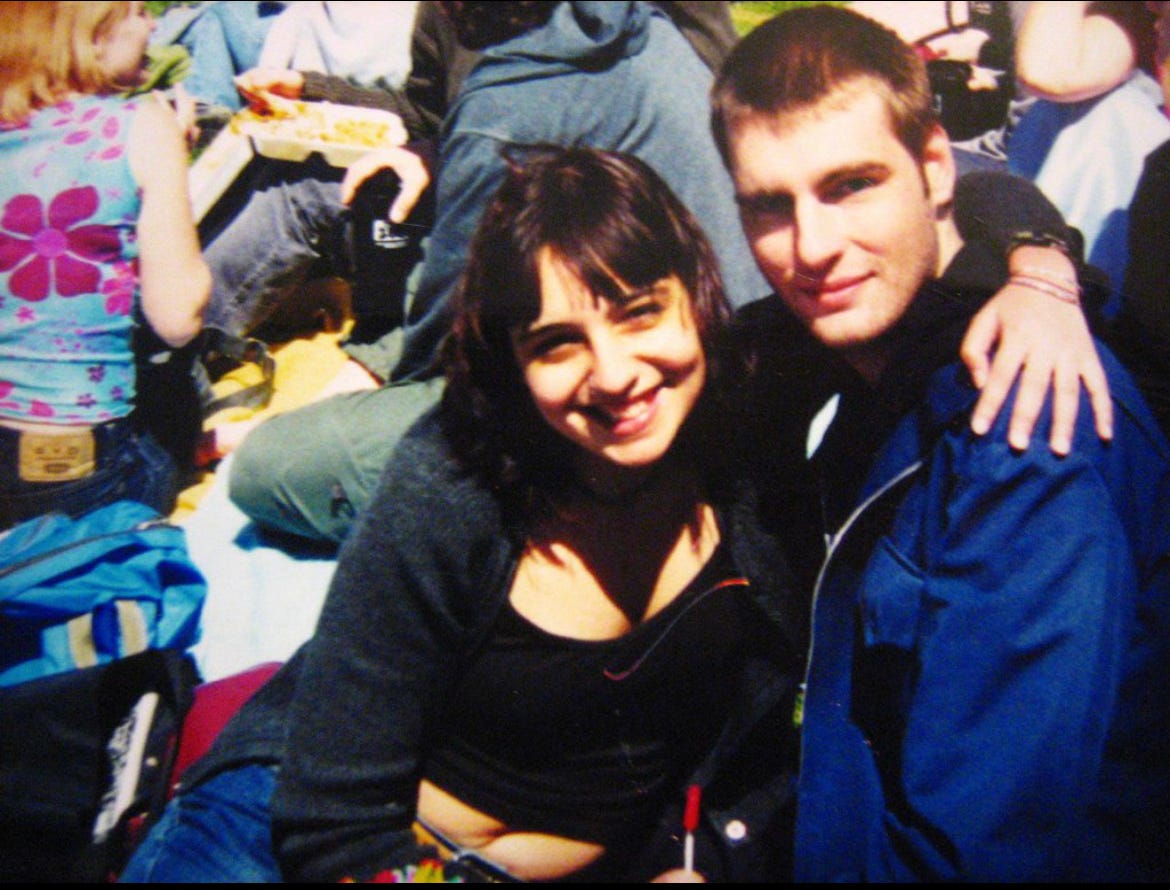

One thing you may, or may not, know about me is that this June will mark the twenty-fourth year I have been partnered with my husband, Andy. I suppose you might call us “college sweethearts,” although we did not encounter each other as co-eds on the quad, but in the basement of the Astor Place Barnes and Noble, where his friend and my soon-to-be manager was interviewing me in the break room for a summer job. I was 20. He was 21. I don’t know what he had been told ahead of time about the interview, but whatever it was, halfway through, Andy entered the breakroom, casually walked over to the water cooler as he sized me up without shame, took one perfunctory sip of water, threw his cup in the trash, and left. I thought,

What a fucking asshole.

Seven or eight years later, when we were new parents, I encountered an article about couples therapy that argued therapists could learn a lot from the way people told the tale of their first meeting, that the way they described this moment could be instructive in gauging the health and the prognosis of their relationship. Fuck, I had thought. What does it mean that my first impression of my husband was that he was a smarmy asshole? I guess jury’s still out on that one.

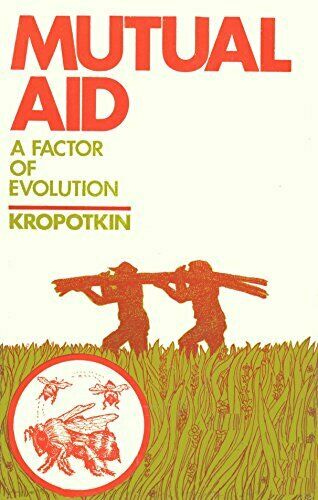

In any event, I got the job, and as we worked alongside each other I realized I had more in common with the smarmy asshole than I would have expected and, to my chagrin, quite a lot of chemistry. As the weeks passed, and the flirtation intensified, I began thinking he could be a good summer fling, given many of my friends were out of town, and separated as I was from the people I had been casually seeing at Vassar. The first time we hung out together alone together, I lugged my original NES to his apartment — where he paid $300 a month to live in 3 bedroom on a tree-lined street in Ditmas Park, directly across the street from the subway station that he shared with two women who were both lovers and opera singers — to play the original Super Mario Brothers. The apartment was empty of the opera singers, but we still plugged in the NES to the TV in his room, where we proceeded to…play Super Mario Brothers. As a date, let’s be real: it was a major flop. There’s only so long you can play an 8-bit video game as young adults, and we got bored and I went home, irritated and wondering whether I had imagined the chemistry as we had shelved travel books and new releases together. But on the way out, I noticed something, which was the 1976 Extending Horizons edition of Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid in a pile on the floor next to bed.

I was thinking of that well-worn copy, of that book, on that floor, when I decided to make a last-ditch effort toward actualizing the flirting some weeks later. As I got ready to leave my shift one evening, a few hours before closing, I asked Andy what he was doing that night.

“Well, I’m closing, so going home?” he said.

“Can I come?” I asked.

“Well, but I’m closing, so it will be late,” he repeated.

“I could sleep over,” I shrugged.

His eyes widened, just barely perceptibly. “Okay,” he said.

Twenty four years and four kids later I can say this: it’s been a hell of a summer fling.

I wonder how many romances Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid figures into. It’s a decidedly unsexy book, 400 pages long of dense, 1902-era prose. I get the sense Kropotkin himself — an anarcho-communist, a prince who renounced his title, and something as a celebrity who was described by Oscar Wilde as “a man with a soul of that beautiful white Christ” living one of “the most perfect lives I have come across in my own experience” — probably had plenty of summer flings. And maybe in 2024, people find Mutual Aid sexier than I’m giving it credit for, but I’m not sure this was true for a whole lot of 20 year old girls in the year 2000 . Still, although college-era Robina had grown out her hair and hair dye, and had stopped wearing her dog collars and combat boots (mostly), she had just a couple years earlier read the same book, and found it electrifying. Seeing the book on Andy’s floor confirmed for her that he was worthy of pursuit.

I myself had originally stumbled into punk, and anarchism, in the immature way many kids do — because I was angry and hurting, and I didn’t know what to do with that anger or that hurt. Growing up as a biracial Pakistani during the time of the Gulf Wars and the first WTC bombing, as a young girl going through puberty in a cultural landscape whose beauty standards involved waif-like white girls with shiny hair in lacy slips crawling across the floor, as someone who had experienced sexual abuse and was still too ashamed to talk about it but felt it burning on my skin like a brand, I believed I would never fit in to the world I inhabited. So I found belonging in a culture that prided itself on not fitting in. Early on I did not understand the political subtext of many of the bands whose lyrics I scribbled in my notebooks and on my sneakers, next to a line from Shakespeare’s The Tempest — you gave me language and my profit on’t is you taught me to curse — that appealed to me equally though I still did not understand enough about colonization to know why. But — at least if you’re me — you can only etch so many anarchist symbols onto subway windows before you start to think you should probably really understand what they mean. And though I don’t remember exactly the path, I was eventually led to Kropotkin.

As with most high school students, I had only been taught one thing about evolution: survival of the fittest. The Darwinist model of natural selection was presented as objective and biological fact. I, a straight-A student despite the anti-establishment exterior, dutifully memorized the theory and didn’t think to question it. But reading Kropotkin was the first time I realized that it was possible that some of the things we had been taught as inevitable and inescapable fact could in fact reflect man-made beliefs as much as nature. I read

if we…ask Nature: “Who are the fittest: those who are continually at war with each other, or those who support one another?' we at once see that those animals which acquire habits of mutual aid are undoubtedly the fittest. They have more chances to survive, and...we may safely say that mutual aid is as much a law of animal life as mutual struggle, but that, as a factor of evolution, it most probably has a far greater importance, inasmuch as it favours the development of such habits and characters as insure the maintenance and further development of the species, together with the greatest amount of welfare and enjoyment of life for the individual, with the least waste of energy.

and my brain exploded. Although it’s hard to remember exactly how much I understood then now, from the perspective of a 44 year old adult who has since done an entire PhD on deconstructing concepts we have naturalized (i.e. race), I know some small glimmer of a lightbulb went off, that I understood in some small way that thoroughly indoctrinating the masses into a narrative of “survival of the fittest” — that competition and brutality over scarce resources is the foundation of all life, the key to how we all have evolved, some hard-wired impulse — conveniently served those who would exploit those masses to horde resources. Kropotkin’s book was a corrective that helped me imagine a different kind of world, a different kind of narrative.1 Seeing that book on Andy’s floor made me think he imagined that world, too. And as it turns out, I was right: for all the ups and downs and challenges the two of us have weathered as a couple, one of the things I value most about our relationship is how deeply we have both wanted to build a life that makes some attempt to divest from the accepted and naturalized but harmful structures and stories that so frequently overdetermine lives in the late stage capitalist hellscape we live in.

A few days ago, I was in a visit with a client who had her baby with me two weeks and five days earlier. The birth was her fourth: the first had been a traumatic surgical birth when she was just 21, followed by a hospital VBAC, followed by a homebirth with another midwife that was both straightforward and transcendent, a revelation in what worlds are possible after two draconian and de-humanized hospital births. This fourth birth was, from my perspective, also beautiful and uncomplicated - 7 hours from start to finish - but because it felt harder and longer than her third, she was still processing these weeks later.

“I think I got in the pool too early,” she told me. “And that’s why it took too long.”

“Really? I don’t think so,” I said carefully. “You know, I really think that idea is a myth - that getting into water can slow things down. If you are in labor, and it’s time for the baby to be born, no amount of water or changing position is going to change that. If water or a change of positions shows us that contractions can space out, it means that it wasn’t time for the baby to be born anyway. Getting in the water doesn’t slow down your labor; it tells you the truth of your labor. And your truth was the baby still had some work to do. Maybe you were just earlier in the process than you thought. But you didn’t do anything wrong and he probably still would have been born at the same time either way.”

“Yeah, that makes sense” she said.

We talked a little more then, about how underestimated the baby is in birth, and how they are not just passive objects being birthed, but active participants who often know more than we do about what they must navigate in order to be born, though that is not the prevailing narrative obstetrics espouses. I shared that I don’t actually believe in the idea of labor stalls, and how in fact what we often term dysfunctional labor, or a labor that ebbs and flows, is actually a labor that is functioning precisely as it should. These ebbs and flows reflect a uterus and the baby working in tandem to give the baby the space and time they need to safely negotiate all the different things they must in order to pass through the pelvis. And then I shared with her something I’ve been thinking about a lot, which is how people often say “I can’t do this” or “this is too much” towards the end of labor.

I used to think this moment — this moment that comes right before the baby is born, this moment where people reach there own limits and then exceed them — was a lessons or a gift. A rewriting of all the myths we’ve told about ourselves. An unlearning of the ways in which we make ourselves smaller than we are, so that we might carry that power and possibility into the enormous work of parenting. But the longer I’ve been doing this work the more I’ve realized that, when people turn to me with their dark wild eyes and say I can’t do this this is too much or shake their heads no, no and whimper, it is less of a lesson and more of a truth.

Because it is too much, too much for one body to bear, much bigger than one person.

Because it’s not one person, it’s two.

When people say I can’t do this it’s too much it’s because they can’t do it alone, because they aren’t doing it alone, because someone else is doing it with them, because they are about to split into two people. Because those two people, together, are in actuality transforming the stories of hundreds, of thousands, of people, into something new. They are made up of not just the stories of survival and love, but stories of broken hearts, of every person who left, of every town that burned down, of every ancestor who died at the precise moment they did. They are alchemizing that into two bodies, two bodies that are the cumulation of all those other each others, each bigger than themselves.

“That’s beautiful,” she said. “I think I’m going to cry.”

And then, after wiping her eyes: “Well, now I feel guilty that I spent so much of theat beautiful process wishing it was over.”

I laughed. “Did you see what you did there?” I asked. “You’re falling into the trap of blaming yourself. And it makes sense, because that is what we’re taught to do. To think of ourselves as one person, and to judge that one person. But what if you could imagine that you were exactly who you needed to be in that moment? What if you could just focus on how how you became two together, taking exactly the time you needed, giving him exactly the time he needed. What if it’s okay if there was fear and discomfort there? What if that’s part of what is beautiful about it?”

This is what being a midwife has taught me, a story of not knowing where one thing ends and another begins. This is what being a midwife has taught me, that mutuality is our birthright. This what being a midwife — a midwife who read Kropotkin as a teen and saw it on another person’s bedroom floor and who did not know it then, but who decided that was the kind of person she would make a whole life with — has taught me:

the foundation of life is not viciousness. It is

not competition, or brutality,

or selfishness. It is

interdependence. it is reciprocal and

collective. it is tender it is soft it is

determined it is hard hard work and

the stuff of dreams.

it is what we do together.

And I’m glad I’m doing it with you.

Love,

Robina

It should be said here that Kropotokin’s theories about mutual aid, while a radical departure from the prevailing Western views about evolution — both social and biological — they were also were not entirely new or original, and were as he himself admits, preceded by a long history of indigenous understanding about the world. However, at that time, I had not had a lot of exposure to indigenous ways of knowing.

I celebrated my daughter’s first birthday two weeks ago and I restart my midwifery clinicals about a month from today — an interesting in-between space to be reflecting on my labor and thinking about the labors I’ll support, and this is exactly what I needed to read. Thank you, Robina ♥️

As usual, your words are a balm and an inspiration. Thank you <3