In which she reads Birth Without Doctors

If a laceration happens during birth, and no one spreads the vagina to see it, does it exist?

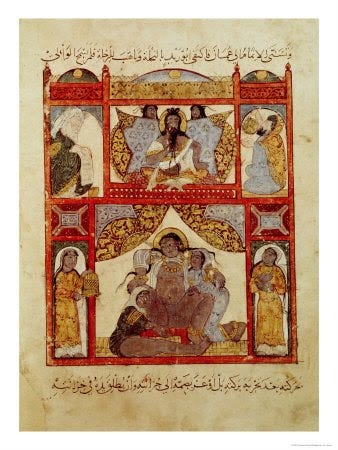

Earlier this semester, in between readings for the postcolonial lit class I’m teaching to the high schoolers and the middle grade book club and Tideshifts1, my midwifery mentorship cohort, I picked up a 1991 book called Birth Without Doctors: Conversations with Traditional Midwives. The book begins

According to the local Malaysian newspapers, traditional midwives…are a very bad thing. Their ignorance and insanitary techniques are the main cause of high maternal and infant mortality in rural areas. They are the cause of problems like premature delivery, mental handicap, and ruptured uterus. They carry out abortions which are illegal and unsafe. If only mothers would be sensible enough not to use their services, and use the government midwives instead, such problems would be a thing of the past.

If you’ve been a subscriber here, or if you’ve followed me over on Instagram for a while, you’ll recognize this is an argument strikingly similar to the ones obstetricians used to vilify American midwives nearly out of existence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, despite the fact that these were claims patently unsubstantiated even by those obstetricians’ own research. Despite their — and their foot soldiers, white nurses’ — claims that midwives were “illiterate, ignorant [Black] women without the first principles of ordinary soap and water cleanliness2” (a truly staggering insult in particular given early OBs had a legacy of killing birthgivers because they refused to wash their hands between examining corpses in the morgue and laboring people’s cervices), at the turn of the twentieth century, wherever midwifery declined and obstetric-led births increased, maternal & infant deaths increased. We know this because obstetricians’ own contemporaneous data show it, with some showing a a 41% increase in infant death specifically from obstetrical intervention and a hospital maternal death rate 13x that of home births.3 In fact, most of the improvements we saw in the middle of the twentieth century when it comes to infant and maternal morality rates had little to do with obstetric innovation and more to do with medical advances that improved life expectancy generally, like antibiotics and better screening and treatment of hypertensive disorders. Even in 1910, we knew that a common denominator in maternal and infant death was poverty (which remains true4, and which, in the United States, intersects with institutionalized racism), not midwifery practice. Still, the solution presented — because the solution being presented was presented by those with a vested interest in driving birth into the hospital, regardless of what their evidence actually said — was always institutional obstetrics, which of course did nothing to address poverty.

In a similar way, Jacqueline Vincent-Priya writes in Birth Without Doctors that the authors of Malaysian newspaper articles fail to address that

the people living in rural areas are poorer, with larger families….Putting the blame on traditional midwives conveniently absolves the authorities from acknowledging this poverty, and covers up what I later found were glaring inadequacies in the medical services provided in rural areas. These articles also never pointed out the more questionable practices in the local hospitals and clinics….Figures are difficult to come by, but there are some hospitals which have an episiotomy rate of nearly 100 per cent, and a high rate of Caesarean deliveries. In many places there is routine separation of mother and child immediately after birth and a consequent very low rate of breastfeeding. Traditional midwives may have their inadequacies, but so too do the government hospitals and private clinics.

There is, after all, nothing new under the (colonial) sun. And while I would very happily write an entire article about medical colonialism, and the way in which Western medical culture and specifically obstetrics —anchored in patriarchy and white supremacy —not only played a foundational role in the violence of settler colonialism, but has continued this violence in imposing its abusive (racist, misogynist) clinical norms in the so-called “neo-colonial” period5, what I want to talk about today is what the experience of reading Birth Without Doctors was like for me, a midwife trained not in the “traditional” midwifery of the country of my birth (since, as we’ve just discussed, that was all but eradicated) or of my ancestry (which from what I understand would not be entirely unlike the Muslim Malaysian and Thai midwives discussed in Birth Without Doctors), but in the Western medical model of midwifery, which stems from a legacy of labor and delivery nursing that “supplements” medicine, acts as an “aid,” or is the “lieutenant” to the “captain” or “colonel” of obstetrics — and which by virtue of that is informed by a paradigm of seeing birth as pathology. 6

One of the things that was so interesting me as I moved through Birth Without Doctors — a book I can find very little background about, and whose author I can find out even less beyond the fact that she has a doctorate (in what, I don’t know) and was by training a “market researcher” (in what, I don’t know) but who then went on to write two other books about birth and breastfeeding after this one — was my own response to the interviews, and imagining the response an obstetrician would have to them. As I read, I found myself fascinated by the process of trying to make sense of what these traditional midwives were reporting from within the framework of my own understandings of birth. For example, it was a repeated refrain by these midwives that when they were called to a birth their first step would be to touch the birthing person’s abdomen so they would “know when the baby was coming.” As someone who has spent no shortage of days sitting on someone’s couch waiting for their baby to come, surely I had been done a disservice by not being trained in this particular skill, I joked to another midwife a few days after reading the first few interviews that mention this. But the deeper I read, the more I realized that what those midwives were talking about was not some magic ability to predict the course of the labor or forsee the precise the time of birth, but to assess and get a sense of where in labor the birthgiver was by feeling the tone of the abdomen, the strength of the contractions — something I’ve done a million times myself. The difference was, in a world where the emphasis isn’t on efficient progress the phrase “know when the baby is coming” means something different. Know when the baby’s coming means asking the question am I pacing this person because they have some time to go, or am I preparing for an infant’s imminent arrival? Because, as one of the midwives casually shared when asked about “abnormal labor,” it isn’t concerning, in these communities, for a labor to take two or three days.

I had a similar reaction to a midwife’s complete confusion over the author’s questioning about tearing during birth; apparently, according to Vincent-Priya, the midwife did not even understand what she was being asked at first, and once she did, asserted that that did not happen in her community. I could imagine an obstetrician attributing this to the lifestyle of the people in these cultures, perhaps claiming that the fact that squatting is a culturally normal way of resting and cleaning in these communities results in a perineum more equipped to withstand the intensity of birth. To that I’d say, perhaps. I could also see an OB arguing that a “lay midwife” in a remote hill station in a systematically oppressed nation wouldn’t know a laceration when she saw one, and to that I’d say, I think the question is whether she’d see one. The truth is, we know that lacerations aren’t a topic frequently addressed in early Western midwifery and obstetric writings; in fact, discussion about lacerations only really appear after the introduction of tools such as forceps. As I’ve talked about before, severe tearing is an obstetric injury, which is to say it is an injury almost always (we never say always when it comes to birth!) related to obstetric intervention, like forceps, vacuum-assisted vaginal birth, and episiotomy. Moreover, we know that the most common way to give birth in Western cultures — on one’s back, with guidance, and, often, anesthesia — increases the likelihood of tearing. This positioning was one introduced by accoucheurs (“man-midwives,” or early OBs) and was the catalyst for episiotomy to begin with; once the perineum became “public” it became more subjected to meddling hands.

That being said, it’s important to note here that in my own homebirth practice, which has a 0% episiotomy rate and a near 0% guided pushing rate (I have employed guidance judiciously at times, most often in a setting where the client is trying to decide, in a very long labor, whether they want to transfer to the hospital), people still tear. Even in a practice where most people are birthing as near to physiologically as one is capable of and want to7 in 2024, people still tear. I have done a lot of work with clients to normalize this as an adaptation of birth, since we have very little reason to believe these kinds of tears represent long-term health issues. Most are minor, and you wouldn’t even know they were there if you didn’t, with your hands, manually spread the vagina to inspect. These physiologically appropriate and common tears are what we Western-paradigm midwives call “hemostatic and well approximated at rest:” that is, they are, when left alone, not actively bleeding, with edges that align exactly as they should. So when I say I think the question is whether these midwives would see, it’s because I can imagine a world in which inspection of the vagina and perineum isn’t valued as a necessary midwifery practice, because it doesn’t make a clinical difference anyway: those vaginas will, in almost all cases, heal beautifully on their own. In fact, I could imagine a world where even if you did inspect, you wouldn’t see a tear as a tear or pathology but simply what a vagina looks like after birth.

But maybe I’m wrong. Maybe these birthgivers never tear. Maybe it’s the squatting after all. Either way, working through this in my mind highlighted the role of paradigm and perspective in understanding birth. A major theme in Birth Without Doctors is the role of spirituality in traditional midwifery; one of the midwives, Vincent-Priya writes, talks about the spirit who guides her midwifery “as if she were another member of the family.” The midwife shares:

[W]henever we are in difficulties the spirit will help us by telling us to keep calm, not to worry and be patient. When anyone is giving birth I only have to call on the spirit, who will show me what to do. To lessen the pain of childbirth I sometimes massage very gently, but if the pain is very bad then I appeal to the guardian sprit. I use the water of a young coconut, over which I chant some prayers so that the guardian spirit enters the water. When the mother drinks the water, then the spirit gets into the body and helps her with the birth.

The midwife continues that she’s never had a problem with babies coming “feet first” or in any other supposedly problematic position, recounting a case where she employed this technique to help a laboring person “where doctors had said the head was in the wrong position:” “I said some prayers over some water and made the patient drink it. After that the baby moved by itself into the right position.”

I was recently mindlessly scrolling on a popular midwifery Facebook group — one that I would never scroll if not feeling mindless because it is basically the worst of what white supremacist paternalistic midwifery has to offer — and a midwife who attends births in the Amish community commented on a post about varicosities bursting during labor or birth (a very rare emergency). She shared that she had once seen this happen and that the bleeding was not responsive to any of her usual treatments, but then the husband of the birthgiver asked if he could try “one more thing,” which was praying over the bleeding. He did, and it worked. “I’ve never seen anything like it in my life,” wrote the midwife. You can imagine what the response was (something along the lines of, “you’ve never seen the body’s ability to clot?”). As with medical colonization, I don’t intend for this newsletter to go down the rabbit hole of the influence or appropriateness of religious practice in birthwork; I myself know I have a bias against the influence of evangelical Christianity (with its patriarchy and white supremacy) on midwifery in the United States. But I do think the response to this midwife’s sharing of her experience beautifully illustrates of the kind of dichotomy of thinking the experience of reading Birth Without Doctors brought up for me.

In Western frameworks of birth, we privilege a technocratic paradigm of the body as, ultimately, legible with scientific knowledge and controllable with scientific technologies. The medical industrial complex is both the arbiter of and the gold standard of “safety.” Praying over coconut water and infusing it with a spirit that can guide birth is derided as some kind of “folk wisdom” that carries with it the potential to kill someone. We popularly think in terms of binaries, with hospital obstetricians representing rationality and objectivity on one end and midwives like the traditional ones of Birth Without Doctors representing irrationality, ignorance, spirituality, intuition, faith, and so on. Of course there are people in the middle, hospitalist nurse-midwives for example. But we think in terms of these poles.

And a big driver of this thinking is the role of evidence. Obstetrics is more rational than traditional midwifery because it has the studies to say that it is.

The problem is, the evidence is never as objective as it thinks it is — and obstetricians routinely notoriously disregard it in favor of their own belief systems and experiences anyway (I remind you here of the statistics with which I opened about early midwifery practice). In fact, while most obstetricians would scoff at a traditional midwife saying she knows what specific treatment an individual postpartum client needs because her guiding spirit comes and tells her in her dreams as anti science, the insistence with which those same obstetricians refuse to practice according to the “scientific evidence” could rightfully also be called anti-science, could they not?

In upcoming newsletter(s)8, I’ll delve into this binary in more depth, exploring the notorious “wooden spoon” obstetrics was awarded in 1979, the woefully understudied emotional elements of practicing birthwork (and its impact on clinical decision making), the push toward data-driven everything both in obstetrics and popular culture, studies like the Term Breech Trial and the ARRIVE Trial, and the hidden costs of all of it (spoiler alert: it’s the humans giving birth and being birthed).

Til then, I remain yours, with love and solidarity,

Robina

👊🏽A final note: if you’re a student midwife or a new midwife seeking a community committed to decolonial, anti-oppressive lenses and practice, I wanted to let you know that applications to the second cohort of Tideshifts: A Midwifery Mentorship Collective are set to go live this winter, and the cohort will begin the week of the Vernal Equinox 2025. Please join the mailing list to stay in the loop about Q&A sessions with participants in this year’s cohort, internship opportunities, and application updates! 👊🏽

We read many more books than this, but unfortunately Tideshifts is just one word, and that was the one I was reading around the time I started Birth Without Doctors.

Reid, Laurie Jean. “The Plan of the Mississippi State Board of Health for the Supervision of Midwives,” Transactions of the Mississippi State Medical Association (1921), 176.

Stats here are gleaned from the White House Conference on Child Health and Protection (1933) as well as:

Loudon, Irvine. Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality 1800–1950. New York: Clarendon Press of Oxford University Press, 1992.

Melissa A. Thomasson & Jaret Treber, 2004. "From Home to Hospital: The Evolution of Childbirth in the United States, 1927-1940."NBER Working Papers 10873, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

See, for just a small taste:

Banay RF, Bezold CP, James P, Hart JE, Laden F. Residential greenness: current perspectives on its impact on maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:133–44.

Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, Cubbin C, Braveman PA. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(3):263–72.

Jardine J, Walker K, Gurol-Urganci I, Webster K, Muller P, Hawdon J, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes attributable to socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in England: a national cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10314):1905–12.

Morgen CS, Bjørk C, Andersen PK, Mortensen LH, Nybo Andersen AM. Socioeconomic position and the risk of preterm birth—a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):1109–20.

McHale, P., Maudsley, G., Pennington, A. et al. Mediators of socioeconomic inequalities in preterm birth: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 22, 1134 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13438-9

As Rupa Marya and Raj Patel write in Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice — a book I recommend unequivocally — “the history of modern medicine is the history of colonialism.”

Nelson, A. The evolution of professional obstetric nursing in the United States (1880′s-present): Qualitative content analysis of specialty nursing textbooks. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances Volume 2: 2020.

I make this caveat here because most of my clients do prefer to have fetal heart tones monitored during labor (intermittently and as unobtrusively as possible, of course), and one cannot argue this is not technically a “disruption” to purely physiologic birth, however minor it may be. As well, I do not discount the amount my presence may represent a disruption to physiologic birth however respectfully and intentionally I show up. As a midwife in the Global North in 2024, my presence does inherently carry an “authority” that my clients mediate in the way they do despite my best efforts to disrupt traditional power imbalances. I am trying to learn in what ways we can reframe power — the power of experience, the power of knowledge, the power of motherhood — as something valuable, something that gives more than it takes, rather than the inherently exploitative, extractive, and corrupting ideas of power many of us in the West have inherited, but that is the subject for another post!

Because let’s be so for real — I originally conceived of this one newsletter as being able to cover all of that, and all I was able to do was talk about my fascination with a book published by the World Wildlife Fund in 1991, so let’s see how long it takes me to actually get through presenting all of the thoughts and research I’ve amassed for you on this topic!

I devoured this so quickly. Thank you, Robina. Tearing during birth comes up so frequently as a major fear for people giving birth in the medical industrial complex (…and of course is used as a justification for obstetric intervention/violence). I wonder whether the people who gave birth with these wise midwives would report that they had any tears, or fears of tearing beforehand.

I always wait to read your pieces till I can really settle in with them, Robina. And then I always end up coming back at least once or twice more and usually collecting quite a booklist along the way—thank you many times over for that!

I’m fascinated (in a rather queasy way) with the strong tendency even more holistic practices of midwifery have to lean into particulation of the body, as if a tweak here and a repair there through the entire process (and culminating with an obligatory tear and then a well-stitched perineum) can somehow optimize birth experiences beyond any healing nature might provide. This was such a wonderful glimpse into a different pace of perceiving what ought to be tended within the body.

(P.S. I had to put my paid subscription on pause, but am looking forward to returning to it in the new year!)