Something that’s been on my mind a lot lately is so-called “expertise” in birth and how we come about it. I myself followed an “acceptable” course, working as part of large midwifery service in a busy public hospital for three years before leaving to attend births at home. I did this because that was what my mentors had done to “gain experience” and I had more or less unquestioningly accepted this as a reasonable approach. The conceit here of course is that attending births anywhere, regardless of the way in which the environment around you approaches it, gives you experience in it.

What’s become apparent to me in the years since, though, is that attending births in the medical industrial complex (“MIC”) is completely different – and requires a different way of knowing, way of interacting with the evidence, and skill set – than attending birth outside of it. Attending births in the MIC prepares you for attending birth in the MIC. Which is to say, it gives you experience in managing birth. Not birth itself.

Let’s unpack this a little by using one specific example, though it can be generalized to a lot of obstetric and midwifery practice.

I once was present in a Labor and Delivery room where an obstetrician was recommending a c-section to a woman who I had, up until this point, been primarily caring for. “I’m sure you understand,” she told the woman, widening her eyes exaggeratedly to emphasize the point, “that it is NOT NORMAL to take an entire night to progress from 6 centimeters to 9 centimeters.”

She repeated this phrase – NOT NORMAL – continually and assuredly in her counseling.

(This was, by the way, the same OB who consistently texted me emojis of a knife whenever she had decided that she was beginning to lose patience with someone’s labor, but that’s a post for another time.)

I return to this moment often, thinking back on the OB’s absolute insistence that this person’s labor was abnormal. She had not one shred of doubt and shared her assessment authoritatively. She was completely certain she knew what was possible of this labor because she was someone who had attended thousands and thousands of labors, and her “expertise” led her to conclude that this kind of labor curve did not end in a vaginal birth.

The irony, of course, is she was wrong.

As it turns out, and as I’ve learned in the years since, the labor curve that she so unquestioningly labeled as NOT NORMAL was in actuality precisely normal for the particular scenario that birther and baby were in (which I’ll return to in a moment). But she wouldn’t know that, because she wasn’t an expert in birth. She was an expert in managing birth.

She couldn’t know what she didn’t know. And her confirmation bias insured that she never would.

I didn’t know then, either. Though I had attended hundreds of births myself at that point, I didn’t yet speak the language of birth yet, hadn’t seen enough physiologic birth to notice the patterns, to know what’s truly possible, to hear the subtle things birth communicates. I spoke the language of the MIC: how to keep birth on a particular timeline, how to follow instructions to induce it in the first place (by the end of my tenure in this hospital, I was genuinely delighted when someone came in in spontaneous labor, because 75% of my job was managing inductions), how to work with 12 different OBs who had different thresholds for different labor curves and different ways of managing complications, how to convince the nurses to let a client labor off of their back even though it would mean continual readjustment of the fetal heart rate monitor, how to support a particular patient’s deep desire for a vaginal birth while being sent threatening emojis of knives. Attending birth in the MIC wasn’t about learning about birth. I didn’t even really learn how to meaningfully value evidence; evidence was always second to hospital protocol anyway. Attending birth in the MIC was a strategic game of how to protect birth from the MIC.

So much of obstetric (by this I also mean midwifery, since midwifery education has been almost entirely colonized by the paradigms of obstetrics) practice and research is dictated by confirmation bias: we are taught to manage birth in a particular way, we get the results we expect from that management, and it fortifies our belief we must continue to practice that way.

Another way to say this: if you always intervene, you never see what could have been if you didn’t.

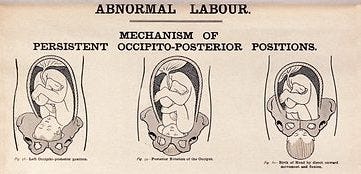

The baby in the labor the OB had labeled so abnormal was in an occiput posterior position, or “OP.” (This is sometimes referred to as “sunny-side up,” which is to say that the baby’s face is looking toward their parent’s pubic bone instead of the tailbone, but I prefer not to refer to refer to human beings as a particular preparation of breakfast food). Research estimates that anywhere from one in five to 68% of labors begin with a fetus in this position, which would indicate it is a variation of normal, but it’s nonetheless pathologized not only by the MIC but by lots of other childbirth experts and educators trying to sell their own brand of intervention designed to prevent it. And it’s true, OP labors are sometimes long and sometimes challenging. The particular curve in this situation – a labor that slows down right when it enters what is supposed to be the “active” phase of labor (around 6cm of dilation) even if this was preceded by an early labor that felt quite intense with frequent contractions – is one of the most common stories for an OP baby. And it’s a story that can end in a safe, satisfying (and often incredibly triumphant!) vaginal birth. The trick is, you have to be patient with it. Whether it’s a few hours, “an entire night,” or even longer, babies often need that time and space to navigate the pelvis (usually to rotate to an occiput anterior or “OA” position1) and be born.

Understanding birth means understanding this particular story and understanding one's job to be, primarily, setting the conditions for someone to pass this time as comfortably and safely (both emotionally and physically) as they can while they await their baby’s rotation.

But working in the MIC, where your expertise lies in managing birth, you could go an entire career without knowing such a thing is even possible. Certainly I myself never saw this kind of outcome while working there, because time is the enemy of industrialized birth.2 At some - usually arbitrary and highly subjective — point someone will always use the fact that a birth hasn’t happened yet as proof that it can’t happen at all.

This kind of logical leap is indicative of the MIC’s approach to birth more generally. Going back to positioning as an example, if you read any studies around OP positioning, they will often begin like this:

Malposition is associated with significant maternal and neonatal morbidity.(Barrowclough et al 2022)

or

Deliveries in occiput posterior position have been shown to have higher rates of adverse short-term maternal and neonatal outcomes compared with deliveries in occiput anterior position. (Foggin et al 2022)

Sounds pretty unsafe, right?

But beyond an “abnormally long first stage of labor” (which, again, has not been meaningfully shown to be dangerous in and of itself) the “adverse outcomes” associated with OP are the following:

Pitocin augmentation

Fewer vaginal births

More surgical births

More instrumental births (forceps, vacuums)

More third and fourth degree tearing

More chorioamnionitis (infection of the placental membranes and amniotic fluid during labor)

More postpartum infection

I’m not sure if you see the pattern here, but every last one is the result of a choice someone made to impose on that labor. Which is to say, we are measuring how dangerous a fetal position is based on how likely it is that that fetal position will result in a human intervention, not by anything innate to that position itself. As much as we like to naturalize obstetric interventions, though, they’re not inevitable consequences. Generally, the main thing they reflect is how comfortable the person managing that labor was with how long the labor was taking.

Take chorioamnionitis and postpartum infection. These aren’t caused by fetal positioning itself (how could they be?), but typically by frequent vaginal exams, which are an iatrogenic (man-made) “consequence” of a long labor. This is especially true if the membranes are ruptured (“water is broken”) when those exams are happening. What is one of the most common tactics providers in the MIC use to speed up a labor? Artificially rupturing the membranes (“AROM”). And what is also an independent risk factor for persistent OP presentation leading to surgical birth? AROM (Cheng et al 2006).3 You can see where I'm going here: providers often cause the very "outcomes" they are attributing to a fetal position.

Another example: OP babies are not themselves likely to cause severe tearing. But forced pushing and instrumental birth are. And why does forced pushing and instrumental birth happen? Because, typically, someone has decided the birth was taking too long.4

Confirmation bias: you can’t know a labor can end in an uncomplicated vaginal birth if you don’t give it a chance to end in an uncomplicated vaginal birth.

The research itself admits this; Foggin et al, for example, conclude “the interaction between delivery mode and occiput posterior position were significant predictors of a delivery with >=1 adverse outcomes, whereas occiput posterior position itself was not.” Which is to say, it’s the choices providers make related to OP position that creates “adverse outcomes,” not OP position in and of itself.

But obstetric practice isn’t guided by research. Even accounting for the fact that most obstetric evidence is skewed from the outset because it doesn’t study physiologic birth, there is actually quite a lot of compelling evidence that birth is safer the less we intervene with it. But if the average obstetric provider doesn’t even know what we “know” from research they themselves produce, how can they ever know what they don’t?

I didn’t know it either. But the longer I practice in a setting where I can observe truly physiologic birth the more I understand the only thing that’s impossible in birth is to predict what’s possible. And that’s something I hope to show you through my writing here, too.

I don’t intend for this to be a long treatise on OP positioning – there is so much good writing about that already – but suffice it to say that the reason why OP labors are often long is because the baby’s head is trying to enter the pelvis with a diameter larger than the diameter they could be entering the pelvis with, so they often need to rotate to that diameter in order to descend and be born.

I’ve written about the MIC’s definitions of failure to progress and failure to descend before, and surely I will again. For now, I’ll reiterate that most of our understanding of “normal” labor curves derive from a few studies that are based not on physiologic birth but births where a vast majority were intervened with by some form of augmentation, pain relief, or both in the first place. In truth, the obstetric community has no idea what a “normal” physiologic labor curve is, because it has never meaningfully studied normal physiologic labor; the “standard” labor is an intervened-with one. Likewise, there’s not been meaningful research about whether length of physiologic labor has any relationship to safety, because most “long” labors in the MIC are, again, augmented in some way, which automatically increases the risk of adverse outcomes. The point is, the MIC is a masterclass in a system that creates a context to produce the evidence that “proves” what they already believe.

Why does having one’s water broken result in more persistently OP babies? Probably because a baby in an intact sac often hangs out higher in the pelvis and has more mobility (thanks to a higher station and more cushioning and buoyancy from the water) to eventually rotate. An OP labor curve I’ve also seen with some consistency is one where the laboring person progresses relatively rapidly to fully dilated (often, but not always, this is in a scenario where the water has broken spontaneously early on in or even before the onset of labor) but then have a baby who doesn’t descend even after many hours of pushing or resting or both. Though in my practice this happens physiologically – not as a consequence of induction or augmentation – if I could choose, I would choose the first labor curve I discussed here (an “abnormally long first stage of labor”) any day of the week, because it’s actually much more likely to result in a vaginal birth, which is why it’s so interesting to me that most hospital providers pathologize length and choose to speed up labor at all costs.

Yes, sometimes it’s because a baby isn’t tolerating labor (or at least what we are measuring of their heart tones aren’t “reassuring”). But that’s usually because the interventions that are associated with a long labor (for example, pitocin) themselves cause undue stress on the baby, not because a long labor inevitably does. A study by Dahlqvist and Jonsson (2017) makes a strong case for this when they conclude that delayed pushing (i.e. having patience with the labor curve) is not associated with significant risk to the baby when it comes to OP positioning.

Works referred to in this article:

Barrowclough J, Kool B, Crowther C. Fetal malposition in labour and health outcomes for women and their newborn infants: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2022 Oct 19;17(10):e0276406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276406. PMID: 36260647; PMCID: PMC9581354.

YW Cheng, BL Shaffer, AB. Caughey. The association between persistent occiput posterior position and neonatal outcomes Obstet Gynecol, 107 (2006), pp. 837-844.

YW Cheng, BL Shaffer, AB. Caughey. Associated factors and outcomes of persistent occiput posterior position: a retrospective cohort study from 1976 to 2001. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 19 (2006), pp. 563-568

K Dahlqvist, M. Jonsson. Neonatal outcomes of deliveries in occiput posterior position when delayed pushing is practiced: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 17 (2017), p. 377

Desbriere R, Blanc J, Le Dû R, Renner JP, Carcopino X, Loundou A, d'Ercole C. Is maternal posturing during labor efficient in preventing persistent occiput posterior position? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jan;208(1):60.e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.882. Epub 2012 Oct 26. PMID: 23107610.

M Fitzpatrick, K McQuillan, C O'Herlihy. Influence of persistent occiput posterior position on delivery outcome. Obstet Gynecol, 98 (2001), pp. 1027-1031

Foggin HH, Albert AY, Minielly NC, et al. Labor and delivery outcomes by delivery method in term deliveries in occiput posterior position: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2022;2:100080.

Niemczyk NA. Maternal positioning to rotate fetuses in occiput posterior position in labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014 May-Jun;59(3):362-3. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12188. Epub 2014 Apr 17. PMID: 24751131.

When I was pregnant in 2020 we were good friends with our neighbors and she was a resident OB at a nearby hospital. I was desperate for her to witness my birth so she could get her eyes on untouched birth. Sadly the timing didn’t work out but I wish people in the MIC at least acknowledged these short comings in their training and in the research.

Great writing Robina! And it is so refreshing to read this and having someone put words on why I don’t want to start my midwifery work in the hospital setting! Thanks