Are you my elder?

On Ina May Gaskin, white supremacy, and inhabiting the spaces we'd rather ignore

About a month ago, I shared a post on Instagram challenging the narrative that people can cause their own labors to be difficult or long because they have somehow failed to “surrender” to birth. So often as a midwife I’ve heard other birthworkers talk about difficult births and conclude that it was the birthgivers’ own mind — whether their fear of pain or the unknown, their resolute clinging to control, their past traumas — that was the main obstacle to birth going smoothly. Parading as a sort of concern or attunement with a client’s emotional life, this quasi-diagnosis is often shared somewhat condescendingly or dismissively as though birthgiver simply has not done enough work to transcend what they ought to have transcended: paradoxically, as if the outcome was controllable had they just controlled their relinquishing of control. And while I could write about just this paradigm, its roots, and its harm for an entire newsletter (and maybe someday I will), what I want to focus on today is how much of the response to the piece revolved not around the idea that this is a paradigm we ought to disrupt and divest from, but the the fact that I invoked midwife Ina May Gaskin in it.

My invocation was actually, to me, a sort of casual one. I mentioned her only to point to her as the midwife who has probably contributed most to the popularization of this narrative (though she herself, I think, mostly inherited it from obstetrician Grantly Dick-Read; more on that later). Her transphobia and racism, I thought, was common knowledge and relatively uncontroversial for an audience reading in 2025. But, I was wrong. For a not insubstantial number of commenters, the two slides of ten involving Gaskin were the major takeaway of the entire piece. Many requested more information because they didn’t know about her “dark side.” I lost a lot of followers. One announced their departure as being because “midwives don’t shit on each other, especially an elder.”

And it occurred to me, then, that it was probably worth writing in a little more detail about the hero-worship around Gaskin, a worship that has apparently persisted despite her transphobia and white supremacy being well known for at least the last decade, and allegations around her and her husband’s Farm becoming more and more public in recent years as well. It occurred to me, too, that critically examining this hero-worship is particularly important right now, when more details about the harms of the Freebirth Society are coming to light (hear my speak on that here; and read about it yourself here), and in the wake of the tremendous loss of Black midwife Janell Green Smith because, in fact, all of these threads are connected. That people can still herald Gaskin uncritically as the “mother of modern midwifery” is emblematic of a culture that also allows grifters to make 12 million dollars off of vulnerable birthgivers (even as they play a role in the deaths of their babies), and whose accumulated stressors contribute to the deaths of Black birthgivers.

Because the fact of the matter is, even the paradigm that inspired me to write the piece — that we must transcend pain and fear in birth — is at it roots a colonial-capitalist, white supremacist belief, one that rests in centuries of false dichotomies between “civilized” and “primitive” birthgivers. And we need to, as a community, interrogate those roots before we accept them as fact. We cannot grow liberatory futures from rotten roots; and so we need to trace our roots deep down and face them.

So let’s.

A hero for w(h)om(b)?

I want to establish something at the outset. Almost every comment regarding Gaskin on that post, which to me can be interpreted as a marker of who has a stake in the narrative around her, was made by people who were, at the very least, white presenting. And I will admit here that my own blithe assumption that my mention of her could be casual speaks to a larger truth: if Gaskin was ever a hero, it was to very specific people. I personally did not feel like I was “shitting” on an “elder” in that post, because she was never part of my midwifery lineage. Many Black midwives expressed similar sentiments after controversy erupted after Gaskin more or less blamed Black birthgivers for their own racial disparities in a talk in 2017 (I’ll discuss this more later); they did not have to grapple with one of their heroes falling, because she never was one.

I first picked up Spiritual Midwifery, Ina May Gaskin’s 1975 book, as a young woman voraciously searching for any and all literature on homebirth that I could find. I was an academic who had first started reading about the history of midwifery academically, but eventually began consuming books about it from a more personal perspective, as I began to fantasize about becoming pregnant and having my own homebirth (and, later, of leaving academia to become a midwife myself). But even as her so-called “target audience,” Gaskin held very little resonance or inspiration for me. I could barely get through Spiritual Midwifery; I also found myself uninspired by her follow-up, Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth (which remains in the top ten bestsellers of pregnancy and birth related books on Amazon even today). What I did read of both was read with a sort of distant anthropological curiosity. And why wouldn’t I feel that distance? It so clearly wasn’t for me. The pictures and stories were all of white hippies. They walked past cows on a farm in labor. Their reality couldn’t have seemed less relevant to mine, a biracial Pakistani who would eventually be giving birth in New York City. I intuitively found myself turning away from stories where white midwives helped white women transcend their brain to “surrender” to their bodies, where white men telling their white wives how marvelous and sexy they were was the only thing that allowed their cervices to open. Something about it, though I’m not sure I could have articulated it at the time, left a bad taste in my mouth. Besides, I knew enough about the history to know that while Ina May Gaskin and her clearly high friends were having orgasmic births on their unregulated birth center, Black midwives were being villainized and regulated-to-eradication all around them (more on this in just a moment).

When people say, “we can’t deny the powerful and positive impacts she’s had,” I wonder, who is “we?” Is Ina May my elder simply because I practice in the United States, and she has indubitably influenced midwifery in this country? Do we assume I couldn’t exist as a midwife in the way I exist as a midwife if she didn’t? An if that’s the definition of an elder, is J. Marion Simms, the obstetrician who performed dozens of experimental surgeries on Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy — the women he enslaved — also my elder? I do, after all, use his speculum routinely (although a good half of my clients now do their own screening for cervical cancer!).1 Where is the line, and who gets to tell me where it lies? What do I owe the people who came before me, and to which people do I owe it?

To be said more plainly: white heroes for white people are not heroes for everyone, and I think white people tend to forget that. 2 That everyone assumes that whiteness is the center.

And this is part of why, I think, people might experience my calling Ina May Gaskin a “white supremacist” as offensive, as some kind of intense, slanderous insult: to them, a white supremacist wears a white hood and cites replacement theory and uses slurs. White supremacists lurk on Nazi message boards and try to get books about the history of enslavement banned and openly admit that they see a Black pilot they hope, “boy, I hope he’s qualified,” or say on-air that“stupid and unskilled Mexicans” should do the menial labor white Americans don’t want to do. White supremacists don’t travel to Guatemala to help people after earthquakes (even if they then steal knowledges from those people and then peddle it is its own), right? White supremacists don’t host Black Panthers on their farms to teach them about midwifery.3

But in actuality to be white supremacist is as simple as to center whiteness as the norm, the standard. It does not mean you have to be overtly racist. It simply requires you be complicit in it, to not question it, to refuse to dismantle some of the foundations on which the overt violences can continue on, undisrupted.

A little context

Ina May Gaskin was never formally trained as a midwife or nurse, or initiated in any real way into midwifery by any kind of elder. In this way her midwifery career is a kind of case study in American individualist culture. Her birthwork was borne of necessity; she began attending births when she was part of a caravan of more than 200 young, white Bay Area hippies who were following her partner (and later husband) Stephen Gaskin on a national tour in which he lectured about the spiritual awakenings he had on LSD. Stephen Gaskin and his caravaners were generally suspicious of medicine, and many of the women who were part of this group had already had traumatic births in hospitals, so when babies began to be born on the road, Ina May simply began attending their births, since she was, at thirty, one of the older members, and already a mother. She attended nine births at this time after a seminar on emergency childbirth measures given by a Rhode Island obstetrician who also provided the group with an obstetrics handbook and supplies. At the end of the tour, the caravaners purchased land in Summertown, Tennessee and named it “the Farm.” There, they created, or attempted to create, a self-sustaining economy where everyone held goods in common and eschewed the use of currency. (All money was to be handed over to Stephen when they joined; no one who left ever received any in return.) They established a printing press, a tofu factory, a working ambulance service and radio communications. They engaged in communal childcare and schooling. Polyamory was common. Divorce, birth control, and abortion were prohibited by Stephen, so his wife had a lot of time to practice her so-called spiritual midwifery, with some mentorship with local family physicians who had experience assisting in home births for a large Old Order Amish community in the area. As she amassed and trained more midwives, Ina May established a birth center in which even nonmembers were encouraged to give birth; in order to discourage abortion, they advertised that Farm would, if asked, adopt and raise the babies of women who gave birth there.

Gaskin’s birth center thrived against a backdrop where the South was concluding its annihilation of the Black granny midwives who, unlike Gaskin, had come from a long lineage of ancestral wisdom and training yet were villainized by obstetricians and public reformers as uneducated and unhygienic. The history of the obstetric takeover of birth, and the racist paradigms it used to consolidate its dominance, has been the subject of my writing pretty consistently for the last few year (see here, here, here, and here, for a start) and I don’t intend for this particular newsletter to reiterate in any real way that long and thorny history. Suffice it to say, obstetrics only began to gain a foothold on birth in the mid-to-late 19th century, when white supremacist fears in the wake of the civil war, the increasing “professionalization” of medicine overall, and a rise of industrialization colluded to drive birth out of the community and into the hospital. The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, granting American white women the right to vote, was a tipping point. In an attempt to demonstrate to these new voters that their concerns about infant and maternal mortality were a priority, Congress passed the Shepphard-Towner Act in 1921. One direct result of this act was the creation of a white public health nurse workforce (which would later evolve into modern nurse-midwife) who became state agents of legal and regulatory enforcement. These white women were tasked with “educating,” supervising, suppressing, and eventually eliminating Black, indigenous, and immigrant midwives. Despite this, “granny” midwives continued to flourish in many Southern states well into the 1950s and 60s, long after they became all but extinct in other states, largely because of segregation, poverty (since these traditional midwives were still open to traditional practices like bartering), and white supremacist terror (one manifestation of which was poor outcomes in the hospital setting; granny midwives outcomes’ were often better as compared to hospital obstetricians’4). It was only with hospital de-segregation and Medicaid reimbursement reform that the attendance of Black women’s births became financially incentivized, and granny midwives were forcibly “retired” by the State right around the time Ina May Gaskin started practicing in Tennessee.

That a birth center constructed by a group of young, white women with enough privilege to not only purchase land, but to gain acceptance by their neighbors and avoid any regulation by the state in the midst of an attempted epistemicide of a Black midwifery tradition speaks volumes to the way in which the project of so-called “modern midwifery” in the United States was inseparable from white supremacy. A bunch of white hippies with no nursing or midwifery training at all required no state oversight, but Black midwives trained in a long ancestral lineage over generations in an apprenticeship model were “uneducated.” But lest you think this is simple backdrop to Gaskin, something out of her control, something simply inherent to her context but not perpetuated by her, let’s talk about the so-called Gaskin maneuver.

Nothing new under the colonial sun

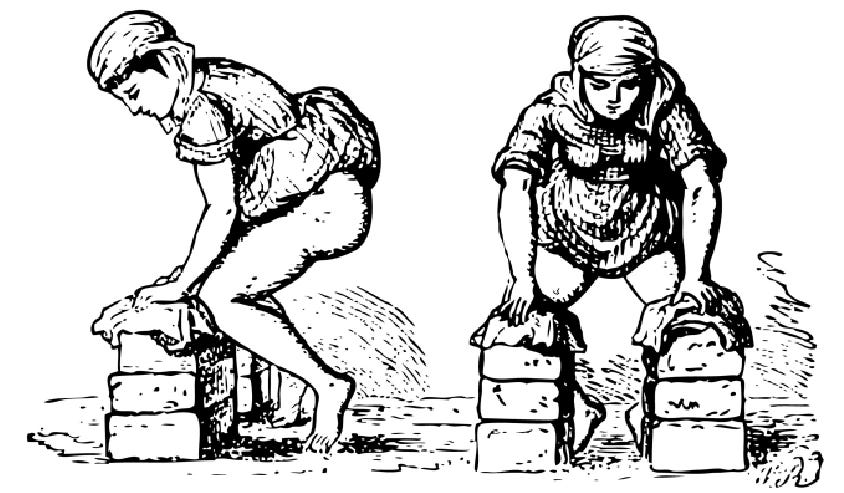

In 1976, a group of women from The Farm traveled to Guatemala to offer aid after an earthquake. During this trip, Gaskin wrote that she attended births with Etta Willis, a Belizean midwife who had worked in Guatemala for many year and was shown by Willis a technique that she, in turn, had learned from Indigenous midwives with whom she worked: turning birthgivers onto hands and knees during a shoulder dystocia. A shoulder dystocia, as I’ve written about before, is when a baby’s head is born, but the body doesn’t follow with the next contraction because the anterior shoulder is impacted or “stuck” on the birthgiver’s pubic bone. Shoulder dystocia can be a life-threatening emergency because it risks deoxygenating the baby rapidly; it is generally accepted that five minutes is the maximum amount of time the head can be out when the body is still unborn before we risk brain damage or death. The technique Willis showed Gaskin helped to quickly resolve shoulder dystocia, because in shifting the diameter of the pelvic opening, it helped to disimpact the shoulder.

Gaskin herself had the opportunity to speak with some of the elder Guatemalan midwives from whom Willis learned the technique. In her recounting of this moment in Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth, Gaskin emphasizes the illiteracy of those midwives and shares that when she asked them how they learned the technique, ‘the oldest of them pointed to the heavens and said ‘Dios. We learned it from God.’” Gaskin then brought the technique back to the States, practiced it on the Farm, and wrote up a study with physician co-authors in the Journal of Family Practice and the Journal of Reproductive Medicine. Subsequently, the maneuver was named after her, and she gained, in her own word “the distinction of being the only midwife in written history with an obstetrical maneuver named after her—the Gaskin Maneuver.”

There is no other word for this but medical colonialism. Gaskin, in effect, stole knowledge from these Guatemalan midwives, then passed it off as her own. In so doing she appealed for legitimacy from the very forces she herself had distinguished herself from — the medical industrial complex — by transforming an oral and sacred tradition into one that passed the test of “evidence based medicine.” Those midwives were illiterate, she was careful to emphasize; she granted their knowledge legitimacy by committing it to the written word. She planted the flag in that land; it was hers.

And she celebrating this as a win for feminism and midwifery while in the same breath contesting the obstetric tradition of naming female body parts and functions after men (“Fallopian tubes,” “Bartholin’s cysts”) as inappropriate. The violences and erasures of colonization, apparently, don’t matter if it’s a woman perpetrating them.

Civilization and its discontents

It’s not totally surprising Gaskin thought indigenous wisdom was hers for the taking. Spiritual Midwifery virtually revolves around a sort of reclaiming of a romanticized “primitiveness,” and frequently refers to the people of the Farm as “settlers” and “tribes,” Gaskin explicitly and repeatedly draws on 19th century medical-anthropological texts to support this paradigm of birth in all of her writing, from using images of “women in traditional societies” to demonstrate the value of upright positions in birth to quoting without comment 19th-century English anatomist Thomas Huxley’s statement that “We are, indeed, fully prepared to believe that the bearing of children may and ought to become as free from danger and long debility to the civilized woman as it is to the savage.”

In this, Gaskin is aligned with the racist tropes that allowed obstetrics to gain a foothold in the first place. Beginning in the late 19th century, anxiety over declining birth rates among white Americans after abolition and in the face of massive immigration led obstetricians to search for ways to make childbirth less agonizing for upper-class white women. The idea that “civilized” women suffered disproportionately in childbirth as compared to the “cruder types” of women was widespread.5 Dr. Frank Newell, an obstetrician writing 1907, summarized these beliefs clearly: “foreign-born” patients who had “not been subjected to…the high requirements (nervous and mental demands) of modern civilization” birthed more easily than "overcivilized” women who were “unfit to withstand any serious strain” and who were prone to “an undue amount of…nervous and physical exhaustion” in labor. This exhaustion often led to nervous breakdowns and fear of bearing future children — a threat to the dominance of the Anglo-Saxon majority. Pain relief methods like Twilight Sleep were developed with these explicitly eugenicist motivations; relieving white women of the pain of childbirth would help them produce more white babies. And it was precisely the promise of this kind of pain relief that accelerated the bringing of women out of community birth and into the hospital.

The so-called “father” of the natural childbirth movement, the British Dr. Grantly Dick-Read, perpetuated these paradigms long after community birth had been all but eradicated in the United States. In 1953, he traveled to central and southern Africa on what may rightfully be called a childbirth safari, to prove the theories published in his 1942 Birth without Fear. His observations of “the processes of birth in the jungle” solidified for him that “the. more civilized the people, the more the pin of labor appears to be intensified.” The births he observed on his travels were, to his mind, more natural, normal, and painless than those “among the white races” that he had “supervised in the modern city hospital.” To his mind, the goal for modern obstetricians were to overcome the “three evils….introduced in the course of civilization” — “fear, tension, and pain” — and which impeded the “natural design of birth.”

In the foreword to the 2013 edition of Dick-Read’s Childbirth Without Fear, Ina May Gaskin writes that she first encountered the book “at the tender age of 16,” that it “set the course of [her] life,” and “prepared [her] to be a midwife in so many ways it’s hard to list them all.” She shares, “when I first began attending births for the women in my community, I relied heavily on the insights I had gained from Childbirth Without Fear, and I still depend on these today.” Yes, Ina May: we see it, in all the women you blame for their own difficult births, and for all the credit you take when your pointed questions about their own traumas have suddenly resolved the emotional obstacle and allowed the baby to be born immediately (as is often narrated in her books).

This is part of why I find the trope of “people getting in their own way” in birth so potentially misguided: because it stems from “knowledges” gained by racist people observing birth through a lens with specifically racist aims. How did Dick-Read know if the African women he observed were experiencing pain? Did he ask them? Did Dr Bernard Krönig, the developer of Twilight Sleep, really observe a “gypsy-woman…dro[p] behind the band to give birth to a child back of a hedge…was[h] the baby in a nearby book and then…run at top speed to catch up with the gypsy-van?”

How do we live in these interstices and contradictions? Where is the space where we can know that a person’s emotional state is of high importance during birth, that their sense of safety needs to be supported, that the physiology of birth is directly impeded by real or imagined threats, that birth is culturally experienced and that our culture fears birth, without resorting to belief systems that have their roots in primitivism, eugenics, and racism?

I think we start by not holding people to a pedestal who have refused to even engage in the question.

Dodging the questions

In 2017, Ina May Gaskin attended a Birth Roundup hosted by Texas Birth Networks. During the Q&A after her talk, registered nurse Tasha Portley brought up “the significant evidence that the stress related to mothers being subjected to racism daily can cause poor birth outcomes.” She then inquired, “I just wanted to know…do you have anything as far as your clientele or just anything to add to that as far as what is going with racism in healthcare as a disparity?” Gaskin replied:

You couldn’t look at our [meaning the Farm’s] numbers and have anything useful to say about it [meaning race and maternal mortality] because the number of African American women would’ve been rather low. Poverty, we’ve got that covered. We were some of the poorest….So poor people ironically can do rather well as long as they don’t, if they eat in a way where they grow what they eat and they’re from sorta farming traditions, they’re going to do well and also if they’re active. Because this has been known for a long time and comes from many different countries that if you do hard work, and this is also born out in rural Alabama and Mississippi and the midwives that I do there who work with people that were very poor and couldn’t afford to pay the midwife and midwife might have been partly feeding them out of her garden and yet they did well and maternal death was rare

Apparently being descended from the enslaved people who literally built the entire agricultural foundations of our country does not qualify one as “being from sorta farming traditions.” She continued, “I think poor nutrition is another factor. And you start piling up things that are risky, then they have a cumulative effect.”

At this point, Portley very graciously offered Gaskin an out by pointedly redirecting her, noting that even when controlling for other risk factors, Black women still have poorer outcomes (I’ve written about this at length here). But Gaskin dug in deeper, lamenting the lack of “really solid evidence” (it’s a body of evidence that is in fact rigorous and accepted) and goes on to ramble about a Black granny midwife, Margaret Smith, who “never had a maternal death” which “shows it’s possible” (what is? Black women not dying in childbirth? I agree.) Gaskin then conjectures that this likely has something to do with religion: “You had more people going to church during her time — that took some of the load off some of the people. Prayer, singing together, lowers stress.” (She does not speak to the fact that Black women were then, and still are, some of the country’s most consistent churchgoers.)

Look, here is what is so discouraging, and frankly damning, about the entire interaction. One can argue about whether Gaskin meant to argue that Black women are responsible for their own poorer outcomes, can claim she wasn’t implicitly saying that if they grew their own food, did more physical labor, had better peer networks, and sang and prayed more, they’d have better outcomes. (She also, it should be said, at some point, rambled on about drug use.) You can try to recuperate her remarks and claim that wasn’t what she intended as much as you want.

But you cannot claim someone as “the mother of modern midwifery” and simultaneously absolve her from understanding one of the most important and significant issues facing American midwifery (and obstetrics more generally) at this time. Which is it? Is she an expert, or is she not? Because any expert in birth should know that it is exposure to racism changes birth outcomes for parents and babies. It is established. It has been established. I myself wrote an entire research project about it as a student midwife in 2013, four years before the so-called mother of modern American midwifery admitted she apparently wasn’t familiar with the concept. We know for a fact that it is not poverty, or education, or nutrition. We know for a fact it is that the stress of racism, passed down intergenerationally. We know it is white supremacy that is increasing the stress on Black bodies their entire lives, including in the womb. We know.6

Here’s the thing that really gets me: that people can hold you up as a hero and an elder and an expert about birth, but not expect you to understand anything about birth for people who aren’t white.

And it’s exactly this kind of ignorance that allows people, nearly ten years after Gaskin failed to appropriately engage in Portley’s question, to continue to ask how Black women like Janell Green Smith can die after giving birth when she was a midwife and should have known enough to stop herself from dying. Or why they ask about her weight or argue about whether it was truly racism that killed her, because we “don’t know” whether the providers who took care of her were racist. It is this kind of ignorance that allows people to ignore this is a collective, not individual problem.

If our so-called experts aren’t beholden to understand the mechanisms by which Black women keep dying in childbirth, then is anyone? And if none of us are aware, then how do we change the structural forces that are killing them? How do we even begin to dismantle the systems that are working as designed?

Then there’s the “women” and children problem.

These aren’t the only problematic elements of Gaskin and her legacy; in August of 2015 she was also one of the most prominent writers and signatories of an open letter to the Midwifery Alliance of North America (MANA) protesting their adoption of inclusive language. The letter relied on tired, transphobic tropes about only women having the ability to give birth and accused MANA of “prioritizing gender identity over biological reality.” It questioned “whether and how these [transgender individuals’] particular needs fit into the scope of practice for all midwives.” It ultimately relies on a false dichotomy by “celebrating” the unique birth giving gifts of women, then implying that gender inclusivity harms these gifts: ““If midwives lose sight of women’s biological power,” they write, “women as a class lose recognition of and connection to this power.” But the two can clearly co-exist.

Then there are recent allegations against the Farm more generally. Dr Ida Santana last year wrote a substack article, “My Mother Raped Me When I was 18,” describing what she calls the machismo of the Farm midwives, and the general neglect and abuse that children experienced there. Though I have never heard anyone accuse Gaskin herself as abusing children, there have been repeated articles by the now-grown children of the Farm generally revealing how often they went hungry, suffered educational neglect, or were denied medical treatment. Others have shared that the Gaskins were verbally abusive to their parents when their parents allowed them to go to school. (See here, here, and here.) Then there was a known suffocation death of a 23 year old woman who was experiencing “a mental health episode.” None of this implicates Ina May Gaskin directly, but it does cast a light on the entire system in which she was operating.

Who gets to tell the story of midwifery?

Maybe I need to say here explicitly that I harbor no ill will toward Ina May Gaskin. In reality, writing this article is the most I’ve ever really ever thought about her for a sustained amount of time. I’d believe it if people told me she was lovely or smart or thoughtful or kind. All of that can coexist with the fact that I’m also not interested in venerating her or her legacy, or the fact that I think so much of her story and her belief system around birth perpetuates an individualism that harms us as a collective. All of that can coexist with the fact that I think we owe it to ourselves and our sense of possibility to dig deeper about the narratives we inherit, to look at what and who is left out, and what work is to be done in those absences To live in the uncomfortable truths and contradictions that birth so beautifully lays bear rather than simply accept the easy and comfortable stories.

Midwifery is one of the most ancient of traditions and professions in the world, with lineages in healing traditions of Babylonia, Egypt, Ancient Greece, India, and the Aztecs; to call one white woman in the late twentieth century its mother is simply short-sighted. Yes, Ina May Gaskin became the face of a paradigm-shifting demand for humane, family-centered care, dignity, and respect in childbirth in the 1970s and 80s. And yes, maybe this laid some of this groundwork for the kind of birth justice I now fight for. But it could only lay that groundwork because it was part of a lineage that destroyed so many other foundations. While still marginalized within a colonial-capitalist, misogynist medical industrial complex, the tradition of white midwifery that Gaskin inherited and perpetuated has wielded disproportionate power over not just professional norms and practices, but the entire narrative of midwifery. And in so doing it has simply replicated that same colonial-capitalist, misogynistic harm. We need to be careful that in idealizing her work, we aren’t limiting our imaginations so much that we do the same.

On that note, if you’re a student midwife or a new midwife seeking a community committed to unlearning the kind of colonial-capitalist, paternalistic thinking I touch on in this piece, you should know that applications to the second cohort of Tideshifts: A Midwifery Mentorship Collective are now LIVE! We just extended early bird pricing through January 26th, admissions close entirely on February 8th, and we begin on March 18th. Generous financial aid is available. I invite you to join us! 👊🏽

Til next time, I remain yours in love and solidarity,

Robina

Dear reader, I have endeavored to keep most of my writing free so as to remain accessible to the widest readership, but my family does in fact rely on and deeply appreciate those of you who still choose to sustain me in doing this work. It actually really does matter to us, perhaps more than you know! If it is within your means, you can upgrade your subscription now:

And if you can’t afford to become a paid subscriber, but want to show your appreciation with a one-time or monthly subscription of a different amount, you can also “buy me a coffee” here.

You can also just show your support by liking, commenting, and sharing this post or my newsletter in general; this kind of engagement helps other people find me as well, and the more readers I have, the more paid readers I have, which means the more I can write, since this newsletter directly funds a significant portion of my childcare. If you’ve been hoping to see more from me in 2026 (which is my wish as well), consider supporting in one of these myriad ways. Thank you. <3

For more on this, see:

Cooper Owens, Deidre. 2017. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Washington, Harriet. 2008. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Doubleday.

I highly recommend Tema Okun’s guide to White Supremacy Culture if you’re not already familiar.

Kamara, Makeda, and Jeramie Peacock. 2012a. “Understanding Racism and Oppression Within the Context of Midwifery Culture, Part 1.” SQUAT Birth Journal (Summer): 18–26.

———. 2012b. “Understanding Racism and Oppression Within the Context of Midwifery Culture, Part 2.” SQUAT Birth Journal (Winter): 20–23.

See, for the history of Black midwives:

Bonaparte, Alicia D. 2014. "'The Satisfactory Midwife Bag': Midwifery Regulation in South Carolina, Past and Present Considerations." Social Science History 38 (1–2): 155–182. https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2015.14.

Fraser, Gertrude Jacinta. 1998. African American Midwifery in the South: Dialogues of Birth, Race, and Memory. African American Midwifery in the South. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Goode, Keisha, and Barbara Katz Rothman. 2017. "African-American Midwifery, a History and a Lament." American Journal of Economics and Sociology 76 (1): 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12173.

Smith, Margaret Charles, and Linda Janet Holmes. 1996. Listen to Me Good: The Life Story of an Alabama Midwife. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Briggs, Laura. 2000. “’Overcivilization’ and the ‘Savage’ Woman in Late Nineteenth-Century Obstetrics and Gynecology.” American Quarterly 52 (2): 246–273.

See for a start:

Davis, Dana-Ain. 2019. Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth. New York: NYU Press.

Giurgescu C, McFarlin BL, Lomax J, Craddock, C, Albrecht, A. Racial Discrimination and the Black-White Gap in Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Review. J Midiwfery Women’s Health 2011; 56:362-370.

Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African-Americans. Ann Rev Psychol 2007; 28:201-225.

Slaughter-Acey, J. C., Sealy-Jefferson, S., Helmkamp, L., Caldwell, C. H., Osypuk, T. L., Platt, R. W., … Misra, D. P. (2016). Racism in the form of micro aggressions and the risk of preterm birth among black women. Annals of Epidemiology, 26(1), 713.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.005

So this was super helpful for me to read. In 2011 when I was pregnant with my first and choosing midwifes, I read a few of Gaskin's books and I was taken in - I was hungry for something to tell me "you can do this." I do remember the one thing that gave me pause was where she said you could just choose during childbirth to "be like a monkey" and that monkeys have no pain in birth - I remember thinking, ok, but their bodies and brains are somewhat different than mine. When I had an emergency c-section after getting to full un-medicated dilatation because the baby was "sunnyside up" I really did think for a long time it was because I had not "let go enough" or had ended up having fear. Reading this post so much clicked about what didn't feel right in those books at the time.

You have written and pulled together threads I have also been tracking in my own way and I'm so grateful!

I have recently started calling myself a "recovering hippie." I am going on 20 years now of evolution from many years idealizing but at the same time skeptical of the hippies/homesteaders I made life amongst from my mid 20s to mid 30s. I'd never heard of home birth until I read Ina May's Guild to Childbirth when I got pregnant for the first time in 2006. I embraced it all- home birth, baby wearing, no vaccines, raw milk, making herbal medicine, growing food, etc etc etc. And I did it all in a small island full of white folks like me - classic hippies running away to try to create a utopia- that is made possible by Seattle adjacent microsoft, boeing kind of company, and folks now with small businesses built off generational privilege and cultural theft- no native people remain on the island. But I digress..... Luckily my social justice roots of my southern family came through and I got off the island to pursue a masters in anti-racist education; and later retrained as a doula - taking very different trainings- one from a black childbirth educator and one from a white hippie midwife (whose work is deeply problematic, but I had plans of writing a comparison piece between the trainings as an educational piece but never came to pass). All this was happening too as covid19 revealed who believed in public health and who believed in white exceptionalism. Thus the hippie to alt right pipeline revealed itself to me...

I recently read The Guardian piece on FBS so I'm glad you wove that in. As absolutely they are all connected. The other term that came to mind about The Farm is "regressive nostalgia;" which we are seeing now with this insane obsession with raw milk and beef tallow that the MAHA/MAGA sect idealizes. I see SO many other movements connected to this.... there's an academic on Substack who wrote a piece about clothing designer/rural dweller/homebirth mom Julie O'Rourke (Rudy Jude) who was seen at an RFK jr event, but also stylistically plays into this trope about regressive nostalgia i.e. a kind of purity culture if you will- and how this feeds into this certain California "natural" mom aesthetic that is so popular (sounds like hippies to me). No matter the style you favor it seems white supremacy is there- whether you want a cookie cutter home in a gated community near a mall church or you want a hand built home in rural Maine- white supremacy.

I think the point about whose elder is key here. I can only speak for myself as a white woman with no true culture to claim that because of this white people take it so personally when some hero they've invested in is toppled- like Ina May. Our cultural impoverishment fuels cultural theft. I do see some people doing good work around this but it sure seems rare and slow.

Anyways- really really appreciate you writing this and putting all these things together. I emailed this off to a couple birth work friends.